Guest post by Megan Giller. Megan is on a journey to explore the real world of American craft chocolate with her digital project Chocolate Noise. Fifteen makers. Fifteen stories. One story per month. Her in-depth series captures the unique moments and personalities behind the bean-to-bar revolution. Subscribe to the series here.

It’s a familiar scene: Silicon Valley, two nerds, a basement, machinery and electronics. Only these particular two nerds weren’t working on retooling a motherboard or creating an app. Todd Masonis and Cameron Ring were huddled over a hairdryer, blasting cacao shells away from nibs. On a nearby table sat a tiny coffee roaster and a half-destroyed tempering machine. They were making chocolate.

Straight out of college at Stanford, the two had started a company called Plaxo with Sean Parker (who you might remember from Napster), and in 2008, after a few tough years, they sold it to Comcast for upward of $150 million. That left them with plenty of time on their hands. “I took some vacation, helped friends start other companies, worked on some iPhone apps,” Todd said. “I spent a month in England digging up an old Roman fort.”

He also started making chocolate for fun. “At first it was the intellectual challenge of, How do you build a winnower?” he explained. “We were used to writing software, but building a machine that could do something physical was new and interesting.” The two friends scoured the internet for information, using sites like Chocolate Alchemy to create the type of chocolate bars that they wanted to eat: two-ingredient bars made with only cacao and sugar that brought out the individual bean’s flavor notes (something that big commercial makers had long tried to disguise).

But unlike their other hobbies, “the response we got from friends was really amazing,” Todd remembered. They gobbled the chocolate and showered compliments on the two friends and business partners. Of course, friends and family will always be your cheerleaders. Asking people to hand over their hard-earned dollars? That’s a different story. So Todd and Cam brought their chocolate to San Francisco’s Underground Market, where it sold out almost immediately.

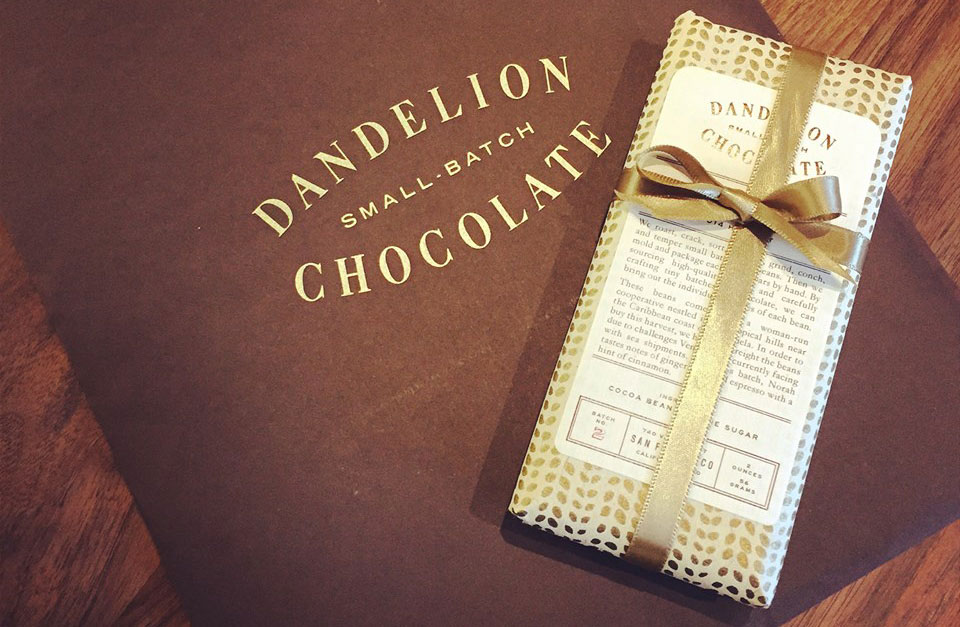

At the same time the two realized that they were part of a bigger scene in America, the craft chocolate movement. “What happened to microbrews and coffee and wine in a sense was actually happening to chocolate,” Todd said. “And we were right in the middle of it.” In other words, people had grown bored with low-quality, overly sugary candy and instead wanted to eat chocolate that they could really taste, single-origin bars that celebrate each bean’s flavor profile, that were made with high-quality, ethically sourced ingredients by an American artisan. Encouraged by the response at the Underground Market, the two friends got to work scaling their business, Dandelion Chocolate, to create more high-quality chocolate.

To the two Stanford grads, that meant harnessing their tech startup know-how and applying it to a new field. They wouldn’t be artists creating a masterpiece but instead pragmatists solving a problem: how to make the best chocolate possible.

When Alain Ducasse opened his chocolate factory in Paris, he invited old-school makers to come try his chocolate. They said essentially to give it 30 years and maybe then Ducasse would have enough experience to make good chocolate. “We don’t want to wait until 2045 to make a good batch,” Todd said. “So we had to figure out how to make good chocolate assuming we know nothing.” Using A/B testing, Dandelion has developed a methodology that allows them to create amazing chocolate. When they source a new type of cacao bean, they immediately set to testing it with multiple experiments in the bean-to-bar process to discover the perfect process for that particular bean. (“The biggest driver of the flavor is going to be the beans and the fermentation,” Todd said. “By the time we get them, that’s already locked in.” That’s why Dandelion spends much of its time and energy sourcing high-quality cacao beans from around the world. However, that’s a different story!)

“The biggest driver based on our experiments is the roasting,” Todd explained. They roast batches at slightly different temperatures or for slightly different amounts of time, then make chocolate bars with those batches. And that’s when the fun begins. Dandelion employees, friends, family — a whole smattering of people — sit down and blind taste-test the different bars, then rate each on a scale of -2 to 2. “Sometimes we mix it up and put two of the same in there to see if people are cheating or lying or whatever,” he said. “But if you get enough people tasting, you start to see that one roast is preferred over another.” It takes anywhere from 10 to 20 batches of chocolate to find the right roast — and one that matches their house style (lightly roasted, two-ingredient bars that highlight the bean’s inherent flavor notes).

After testing other variables like the right time to add sugar (after one hour of grinding the nibs or after three hours?), they’ve found the right process for that bean, resulting in fantastic single-origin bars from places like Guatemala, Papua New Guinea, and Venezuela. One maker usually spearheads the experimentation for each bean, but after it’s finished, any Dandelion employee can make the perfect chocolate bar, because they have a documented, failproof process for that bean. Right now the company has between 10 and 15 chocolate makers, a vastly different model from other artisan companies, where the sole chocolate maker is viewed as an artist.

However, Dandelion still has scaling problems. They make about 12,000 bars per month, but that’s not enough: Right now over 500 stores across the country are on the company’s waitlist. They simply can’t produce enough chocolate to satisfy the demand. Dandelion’s wholesale manager says her job description is “customer disappointment management,” because she turns people away all day. Big national companies have approached Dandelion about carrying their chocolate in their stores, but the artisan chocolate maker hasn’t been able to add new wholesale customers in over a year.

It’s been that way since the beginning: When they opened the factory shortly before Christmas in 2012, they weren’t expecting much of a fuss. They thought maybe once in a while someone would drop in and buy a bar but that mainly it would be a behind-the-scenes factory. Instead, “We had to ration the bars,” Todd said. “We told people, ‘You cannot buy more than five chocolate bars per day, because it’s not fair to everyone else.’ So people would come with their friends, who would buy the bars, or they would try to trick us.”

Part of the problem is that Dandelion makes much more than chocolate bars. They also run a storefront with drinking chocolate and treats like chocolate brownies and cookies, which requires just as much chocolate as the bar side of the business. “We built what we wanted to exist,” Todd explained about his motivation. He remembered going to Paris and sitting down to enjoy a hot chocolate, and he wanted to bring that experience to America. To him that means high-quality chocolate bars and impeccable drinking chocolates and pastries that you can savor in the store, as well as chocolate classes and educational programs. The result is a magical storefront full of delicious smells, treats, and pretty happy people.

“It would have been easy if we just wanted to make more money,” Todd said. “We throw out a lot of chocolate that we’re not happy with.” But he has no reason to compromise. “People said, ‘What would you do if you were really successful and you could do anything?’” he remembered. “I said, ‘I’d probably start a chocolate factory.’ In some sense I’m already living the dream. I’m not looking for anything else,” he said, adding that there are much easier ways to make money in Silicon Valley than to make chocolate. “There’s no inherent pressure to keep going for money,” Todd said. “We want to do something awesome for the world and help redefine the space and the bean-to-bar movement.”

Find out how they plan to do it by reading the full story on Chocolate Noise.

Megan Giller writes for publications like Slate, Food & Wine, and Texas Monthly. She’s currently exploring the world of American craft chocolate through her digital project Chocolate Noise. Read more of her work at megangiller.com or follow her on Twitter.

Megan Giller writes for publications like Slate, Food & Wine, and Texas Monthly. She’s currently exploring the world of American craft chocolate through her digital project Chocolate Noise. Read more of her work at megangiller.com or follow her on Twitter.