Illustration by Melkorka Kjarval

Illustration by Melkorka Kjarval

Grass-fed beef has become a household name, but despite unprecedented awareness and demand, many American producers find themselves struggling to make a living, battling against infrastructural flaws brought about by decades of agricultural consolidation. Retail chains like Wegman’s (here in NY) and Trader Joe’s have recognized the demand for grass-fed beef, but instead of sourcing from American ranchers they import it from South America.

Many barriers exist between producer and plate, which are a result of profound consolidation in our meat packing industry and a breakdown in processing and distribution channels. Logic dictates that an increased demand for grass-fed beef would be enough to facilitate a market for it, but in many cases demand in itself is not enough.

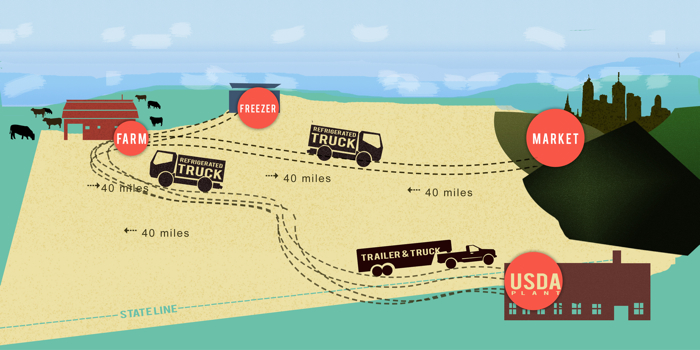

Direct sales require a lot of capital and risk, and can be difficult for ranchers who live far away from large cities because of lackluster local demand and high shipping costs. Little infrastructure exists for local meat sourcing, and farmers have had to create distribution channels themselves.

Farmer Craig Rogers, of Border Springs Farm in Patrick Springs, Virginia shoulders all the distribution work himself, driving thousands of miles each week to deliver his high quality pastured lamb to top chefs in New York, DC, Charleston and Atlanta. “I spend $2500 per month in gas to distribute my lamb and lose money doing so,” he said.

Illustration by Melkorka Kjarval

Illustration by Melkorka Kjarval

Tennessee farmers Kimberlie and Ralph Cole of West Wind Farms find that direct marketing and distribution is a whole other job, and for full-time farmers the burden can be too much. Kimberlie laments the amount of time driving and the fatigue from so much energy going into distribution. “At the point of product distribution, so much energy has already been devoted to production and processing,” she said. “Ralph and I both realize we are at a very high risk of falling asleep at the wheel and having a major accident,” she added.

They have had to get creative with their distribution, even hiring their own consumers to sell their meat at farmers’ markets and paying them with meat. Kimberly was quick to note that they could only afford their farm and land because it is so rural, and with tightening definitions of local she fears that many urban markets and consumers are cutting out farmers who are doing it right in very rural locations:

“Urban people don’t recognize that some farms exist solely because they are remote. We would not have been able to afford a farm closer to an urban area, and we cannot survive on sales within a 100-mile radius of us. Excluding farms outside a 100-mile radius from direct marketing opportunities will kill small farms in remote rural areas that have no other viable markets.”

When there is no local demand

Issues of distribution are especially acute in America’s west, where grass-fed systems could arguably benefit us most. In Colorado and Wyoming, where 700,000 cattle are born each year, it is rare that a rancher finishes his own cattle, and for those who are doing it exclusively on grass, finding a market can be extremely difficult.

Vast arid grasslands are being utilized and revitalized by ranchers like Rod Morrison of Rocky Mountain Organic Meats, whose rotational grazing practices guard against drought and rebuild soil fertility. Yet Rod has encountered many challenges in finding a market for his beef, and also feels that the local movement hurts organic producers like him who do not have local demand:

“For us it became very clear we were not going to be able to compete using the old meat paradigm. We needed to connect directly with people that want this product, but cannot find it locally. Now everyone wants to argue the carbon footprint of home delivery. Home delivery does not even come close to the combined impacts of consumers driving to market to buy conventional meats.”

Currently, Mr. Morrison sells direct via his website www.rockymtncuts.com, but feels that the future of his operation rests on finding a partner that can buy a certain amount of ground beef each year.

Colorado rancher Cathy McNeil is caught in a catch-22. Her product is too expensive for her rural neighbors because her community lacks local jobs, jobs that would be created if ranchers like her could become more financially viable:

“It’s been difficult establishing local markets, especially here in the San Luis Valley, where the five counties within are the poorest in the state, with one of them being one of the poorest counties in the entire U.S. (It is known as the “Appalachia of the west.”) Therefore, many of the local people can’t or won’t pay our prices, which are higher than commercial beef because the processing costs are so much more, and as you know it takes a lot of time to finish out a steer on grass without growth hormones.”

Lack of Processing and Distribution Channels in Northeast

Even in New York, where we have arguably the biggest and most lucrative market for beef (most of American prime grade beef is consumed in NYC) there is no organized market for grass-fed beef and farmers have to sell their product directly. In central New York, where there is a dearth of USDA processing plants, direct sales are hampered because processing becomes a logistical challenge.

Mike Baker of Cornell University is conducting a grass-fed beef study (three of our steers were included in this). It was not until buyers were secured for the steers in the study that it could begin. Dr. Baker stressed how there is no market or distribution system set up for American grass-fed beef, so many producers have to do it all on their own, which for most is impossible.

There are many other ranchers that want to switch to grass-fed finishing, but feel that it is too great a risk to shoulder all on their own. Many carry freezer beef, but still sell to feedlots to make a living. It is a rare rancher that can successfully navigate all of this. Many ranchers who want to make the switch find themselves in unsupportive communities, with inadequate processing alternatives and retailers unwilling to help them sell their products.

Lack of USDA slaughterhouses has become a well-known issue in the good food movement, but many do not realize the distribution issues that sustainable/organic farmers face, especially in rural regions where land stewardship and vibrant local economies are needed most.

As a grass-fed farmer, I know the overwhelming obstacles that stand in the way of profit for my family. If not for the lucrative NYC market we would not be as successful. We need more independent “middlemen” to help facilitate business connections between ranchers and consumers.

Two prominent retailers, Whole foods and Walmart, have made a commitment to sourcing from grass-fed ranches and medium sized farms, but the future will tell if infrastructure set up by these large chains benefits producers. We have to bring increased awareness to issues that face direct- market farmers, especially those out west who need our support. We also need to encourage our retailers to help create local systems, and keep a close eye on those that claim they do.

This piece was originally posted at Green State Fair.

Ulla Kjarval is an NYC based photographer, food blogger and grass-fed advocate. Her family operates Spring Lake Farm in Delaware County, New York. Ulla’s blog is entitledGoldilocks Finds Manhattan.