Today, Food+Tech Connect launches the first in a series of monthly interviews with leading food and tech investors.

Over the past year I’ve spoken with 100+ food tech entrepreneurs, many of whom are building products based on what they believe can get funded- focusing mainly on restaurants and recipes. Yet, many of the investors I’ve spoken with feel there is a lack of interesting and investment-worthy companies in the food tech space, in part because they seem to get approached by companies whose technology is restaurant and recipe based.

Our food system is rife with challenges, which makes it an entrepreneurial gold mine that extends way beyond the increasingly saturated restaurant and recipe markets. One of our goals at Food+Tech Connect is to highlight these problems and the people tackling them with innovative technology in hopes of inspiring talented entrepreneurs and technologists to think bigger and to build products that solve real problems.

This series is designed to introduce you to the investors that are interested in food, and give you an inside look at their investment goals, criteria, and how they would like to be approached.

My first interview is with angel investor, startup advisor, and serial entrepreneur Ali Partovi, who recently wowed both the food and the tech communities with his Earth Day TechCrunch article: Food is the New Frontier in Green Tech. While many know Partovi for his impressive advisory and investment portfolio including companies such as Facebook, Zappos, Dropbox, Tellme, and Opower, he is now focusing his energy on sustainable food and agriculture, particularly the carbon footprint of food production. According to Partovi, his recent angel investments in Farmigo and BrightFarms, as well as his website Fixfood.com, are just the beginning- he intends to spend the next 5-10 year investing in this space.

Partovi generously gave me an hour of his time, diving deep into his interest in the food tech space, his investment priorities, and the best way to approach him with an idea.

__________________

Danielle Gould: How did you get interested in the food tech space?

Ali Partovi: My wife, Gina, was the first one of us to get into the food space and was initially inspired because we have kids. She started reading The Omnivore’s Dilemma and began focusing on the foods that schools are feeding our kids. I started reading the book over her shoulder and then I wanted to read the whole thing myself- it was for sure the inspiration for me. I found myself starting to feel angry. As an affluent, educated person, I had failed at doing something as basic as keeping my family healthy with natural food. It just seems like there are real market and government failures in a first-world country like the United States, when somebody with money and education still needs to be so conscious and attentive to avoid getting fooled into buying something that may not be good for them. Why should it require so much energy, effort, and money to eat food that’s good for you? So, I started thinking more about how these systemic problems could be fixed.

I really started feeling this on two levels- personally and systemically. Personally, I’m on the organic end of the spectrum, the kind of person who shops at Whole Foods, but began realizing that even organic isn’t as perfect as we think it is. On a larger level, I began thinking about what 90% of America is eating. The McDonald’s corn-based diet that most of the country eats is even more deceptive and even more problematic, and there is even more room for improvement.

I’ve thought a lot about both, and I really want to get involved more on the latter side. People like myself don’t ultimately need that much help improving what they eat, because at least they have the benefit of money and education. Whereas the majority of Americans can’t afford to spend the money it costs right now to purchase all organic food and that’s because the regulatory framework has created a very un-level playing field.

DG: Your first two investments in the food tech space, BrightFarms and Farmigo, are tackling two of the major food system challenges: energy consumption and the carbon footprint of food production, and food distribution. What interests you about both of these companies?

AP: From an investment standpoint, Farmigo was an earlier investment and was much closer to my comfort zone of technology, which is where I have much more experience investing. And although Brightfarms is more of a new technology, I still have some level of comfort, if nothing else because Paul Lightfoot [CEO of Brightfarms] has a technology background and BrightFarms does have some technology aspects to it in terms of over time how to best optimize the operation of the installations. They are two very different investments. Brightfarms is much more capital intensive. It’s much more about raising money to build a lot of sites over time. It’s also a very long sales cycle, and the biggest risk is the sales cycle, because you might not be able to close deals fast enough. Whereas Farmigo is not very capital intensive and has a very short sales cycle. But Farmigo has a much longer path to getting to large scale.

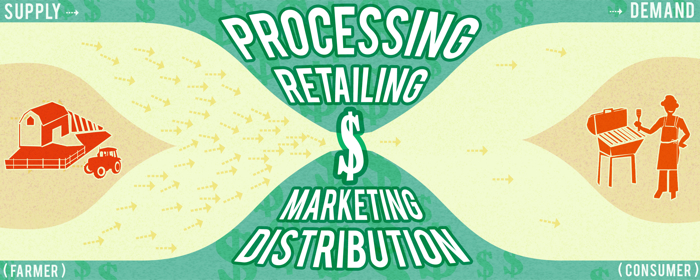

Another thing that attracted me to both companies is that each can be successful starting small, but both also have the potential to grow to enormous scale and transform the food chain. Farmigo is already making money enabling just a few hundred local farms to sell directly to consumers, and they have the potential to change the way millions of people buy food. Likewise, BrightFarms can make money simply operating a single greenhouse-based farm, and if that works, it can expand to transform how entire regions of America source their produce.

I suppose one other common aspect that interests me about both companies is the intersection of food reform and environmental impact. I do care about health care and other factors that are significant in the food space, but between the different aspects of food the environmental footprint is what is most interesting for me, and is the angle I focused on in the TechCrunch article. I think both BrightFarms and Farmigo fall into that category, and if they are successful, they will reduce the environmental footprint of food, each in their own way.

DG: What problems related to food reforms and environmental impacts have you looked at? What problems would you like to see solved?

AP: By far the big one is the corn-based industrial agriculture system which has an enormous environmental impact both in terms of fuel consumption and related carbon emissions, particularly in the US. Beyond the US, I have looked a lot at land use change. It is tricky because it is very difficult to argue that less developed countries should not do what we’ve already done before them, in terms of clearing out undeveloped land for agriculture.

These seem to be by far the big places where environmental impact of food production could be reversed. I suppose the third category would be industrial livestock operations and large scale efforts to provide for an alternative.

DG: Are you looking to invest in additional companies in this space?

AP: I am certainly interested and I’ve been learning on an ongoing basis. The area I know least about is the international land use changes in terms of reforestation. I hope that there will be really scalable efforts that can help figure out an alternative, but I haven’t discovered any to date.

Domestically, the factory farm and corn systems go somewhat hand in hand. The corn system feeds the factory farms, but the factory farms are what create a lot of demand for the corn. I guess the area that I find particularly enticing is to enable scalable pasture-based livestock production. Whether it’s a single company or a series of companies or the equivalent to a larger scale Niman Ranch. Essentially, the more we can transition to eating animals raised on pasture directly, the more we will be able to reverse some of the negative impacts of both factory farms and the corn based system.

DG: Is grass-fed beef an area of investment you are particularly interested in?

AP: I am definitely interested in investing in grass-fed beef. I have been learning about several new companies and existing companies in that space. Marin Sun Farms, the one I mentioned in the TechCrunch article, is probably the best known grass-fed beef ranch in the Bay Area. They may not be the highest volume, but I think they are the most conservative in terms of their protocols. I am definitely interested in learning more about it and investing in something that can do it on a larger scale. I think it needs to be hand in hand with government support as well, like some sort of grass subsidy that levels the playing field with the corn-fed ranchers.

From every conversation I’ve had, it seems to me that grass-fed beef, and pasture-raised livestock more broadly, is a huge opportunity for capital investment. The market is not developing as fast as it should because there’s not enough capital flowing into it. This is a classic problem whenever there’s a rapid-growth opportunity in a traditionally slow-growth, capital-intensive business. I experienced the same thing first-hand when I invested in early Zappos: the company was posting insanely rapid growth, doubling every year, but it was always on the verge of running out of money because it didn’t have enough capital to keep its warehouse stocked with shoes. The same situation applies for many pasture-based ranchers and livestock operators: they are seeing meteoric growth, and they don’t have enough money to expand their herd and land fast enough to keep up with demand. And in both cases, the typical investors are hesitant because they’ve never seen a shoe store or farm that needs so much capital to grow so rapidly. As a result, supply of pasture-raised meet and dairy consistently lags behind demand, which means there’s a systemic shortage. This causes prices to be artificially high on a product that should really be cheaper because it doesn’t involve all the fossil-fuel inputs or waste-management issues.

I think there’s a particular opportunity to build a national grass-fed beef brand. Beef is really a seasonal food, because cattle have the most fat (and flavor) right after peak grass season. This puts grass-fed producers at a disadvantage, because at the wrong times of year grass-fed beef will be leaner (and less flavorful), whereas corn-based factory farms have trained people to expect pime beef year-round. There’s an opportunity to overcome this via regional diversification, because different parts of the country have different seasonal variations. A national brand could provide grass-fed beef that’s “in season” year-round by drawing cattle based on regional variations in peak grass seasons. This wouldn’t be 100% “local,” but it would involve far less transportation than shipping corn to feed cattle.

I’ve also been considering investing in slaughter houses. It’s definitely not a pleasant area, but it is one of the bottlenecks for pasture-raised livestock.

DG: What criteria do you consider when evaluating potential investments? Does your criteria for food tech start-ups differ from investments in more traditional web companies?

AP: I guess it has to, because in food tech I care just as much about the mission as I care about profit. I’m particularly interested in making investments that will expand the supply of sustainable, organic food. Industrial, factory-farmed food is over-produced in the US, and perceived as more affordable; whereas organic, sustainable agriculture is under-produced, and perceived as a luxury for the rich. The reality is that sustainable agriculture is (almost by definition!) more economical to produce, especially in a world of limited resources; and demand for local, organic, sustainable food is growing rapidly. Yet various market skews impede the supply from expanding rapidly enough to meet the demand, resulting in higher prices. This creates opportunities for profit while helping close this affordability gap.

Regardless, I’d say that across the board my number one criteria is evaluating people. What I’ve found from investing in web companies for over more than a decade now is that, looking backwards, the ones that did really well were the ones where the people were great. Whether I knew them in advance, because I had worked with them, or had received an introduction from someone I trust, those are the investments I wish I had put more money into. And the ones I wish I’d put less into were the ones where I just didn’t know the people, but I liked the idea.

I don’t think I’m better than anyone else at evaluating an idea. Whereas, I do feel like I have an edge at evaluating people, and I trust my assessment of people much more than my assessment of any given idea. Zappos is a perfect example. Tony Hsieh [CEO of Zappos] was my partner in my first startup and we had worked closely together for years. I have to confess, at the time I decided to invest, I had never bought a shoe without getting to trying it on and it was hard to envision people buying shoes without getting to try them on. So, I was drawn to this investment because of Tony, not because I believed in the shoe idea. And I kept putting more and more into it over time, again, because of Tony. There were things about the idea that sounded promising, but if it had been some stranger who I didn’t know much about, I would have been much less willing to invest.

Same thing with Dropbox. The concept had enormous potential, but there were already like a dozen other companies competing in this space. How could you pick a winner? Why did my brother and I invest in Dropbox? Because of the founders – these two young guys from M.I.T. and the prototype they had built really impressed us. They were perennially sleep-deprived, and they reminded us of ourselves, in terms of work ethic, product intuition, and technical acumen.

The investments I’ve made in other cause-related areas such as green tech and education, have also involved people I know. I am an investor in a green tech company called Opower, which essentially applies social peer pressure techniques to help you reduce your electricity consumption, by showing you how much you are consuming on your bill, what you can save on it, and how you compare to your neighbors or peers. At the time I was evaluating the idea, I didn’t know anything about energy and utilities or anything about the energy space. But I knew Dan Yates really well and I was investing in him. In hindsight, it’s been a very successful investment – they’re forecasting that Opower alone will save more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire solar industry combined. Again, at the time I was investing, I couldn’t have told you how successful they would be. All I could have told you is that he is a really solid guy and I would invest in almost anything he does.

DG: Are you looking to be approached by Food Tech Startups? If so, how do you prefer to be pitched ideas?

AP: I guess I would say yes. I’m always eager to learn more, but being relatively new to the food and ag space I’m still in a ‘getting my feet wet phase.’ I’ve already been approached by dozens of organizations since my article posted, and it’s going to be a gradual process for me getting more and more comfortable with the space before I jump into it with both feet. Although I have really learned a lot, I still have a bit of insecurity as to all the things I don’t know. So as I get more secure with my own knowledge in the space, I’ll probably be doing more.

As to how I prefer to be pitched, I prefer email as opposed to a phone call, Facebook message, or voicemail. But more importantly, the most successful inquiries are the ones that come through a personal introduction of some sort. Like yourself — the introduction from Paul inherently made me more likely to speak with you. [Full disclosure- I was an employee of BrightFarms and was introduced to Ali by BrightFarms CEO Paul LightFoot]

DG: How actively engaged are you with the companies you invest in?

AP: I would say very actively engaged. My twin brother and I do invest together as a team, so usually one of us is more active than the other on any given company, although there are some where we’re both very active, such as Dropbox. We’re both very passionate about it and spend a lot of time with them. It also varies based on what the company needs at the time. If the company is in the middle of something that really fits with my area of expertise, then I’ll spend a lot more time with them verses if they are at a stage where they don’t need as much help, or the help they need doesn’t match with what I’m good at.

DG: Agriculture is generally a low margin industry. I’m curious to hear about what your target IRR is and how willing you are to sacrifice large returns for the greater good?

AP: I don’t really approach investing with money as the first focus. My main goals are to have impact, to have fun, and to learn. Those are my three priorities — in that order. Making money, is perhaps a way of keeping score, especially with regards to impact. Usually how much money something made is a good indicator of how much impact it had, although that’s not always the case. I do care about how much I learn and how much fun I have, for both of which money doesn’t have any real indication at all.

I don’t focus on IRR as much as if I were an institutional investor and had limited partners that I had to report to on how well an investment did. I’m investing my own money. I co-invest with my twin brother quite a bit, and the two of us share the same priorities more or less. We do look at the IRR once in a while, mainly, I suppose, for fun and because we’re naturally competitive and like to know how well we’re doing. But it’s not what determines how happy we are. When you’re investing your own money, there’s a mix of some things that may be higher risk and higher growth, while other investments may be safer and lower growth. Agriculture might be lower risk and lower growth than technology, but that’s fine for that to be part of my portfolio.

Having said all this, agriculture may be low-margin, but it isn’t necessarily low growth. There are parts of agriculture that seem to be experiencing very high growth. The entire Organic industry has had double-digit growth for decades. You have the potential for very rapid growth when you introduce a new technique that is successful, whether it’s literally a new technological technique or something new like feeding on grass. Wherever you are seeing the introduction of new techniques, there is also the potential to make a lot of money. So I do think there are very high growth opportunities in agriculture, and that can make up for low margins. However, this also means that different investment structures make more sense – it may not fit the traditional VC model or the traditional bank loan model.

Anyway, for me personally, I believe that if I invest in a new technique and a new way of doing things that is better in some way, whether it’s more economically efficient or environmentally efficient, then I’ve had a lot of impact, not just on my bottom line but also on the greater good.

DG: You mentioned that one of your goals is to learn a lot about this space. How have you been educating yourself?

AP: A mix of reading and meeting a lot of people. Every time I meet someone, like yourself, I ask questions and just randomly work my way towards new groups, or communities, or networks within the space. Each person offers a little bit of a different perspective, or new information, and so on. I’ve also been reading books, blogs, and university research papers. Some of this research was because of the article I wrote, but I’ve particularly studied up on the carbon footprint of livestock. But the most fun way to learn is from meeting people.