Guest post by Rebecca Chesney, communications and research manager, Institute for the Future. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views of Food+Tech Connect.

In their contribution to Food+Tech Connect’s future of dining series, Food52 Co-Founders Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs advocated for a GitHub approach to home cooking, a way for cooks to track changes to recipes and build on each other’s ideas. Think of it as a collaborative and dynamic global cookbook, created by everyone from a Michelin starred chef to a student learning to eat on a budget.

The ability to connect the digital and physical worlds gives us opportunities to link people, skills, and knowledge together in ways we’ve never seen before. Indeed, when Institute for the Future’s 2014 Ten-Year Forecast set out to imagine ten projects that would change our paradigms in the next ten years, we included a Wikipedia for Making, a universal grammar for making anything.

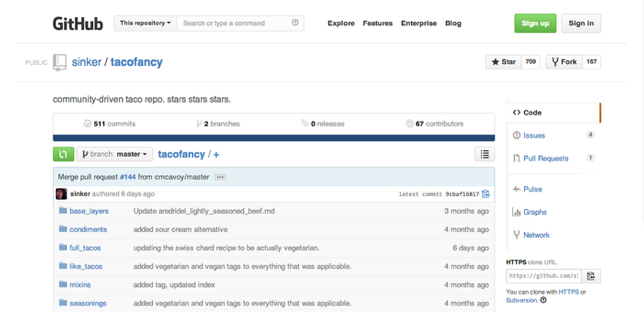

By sharing code and tracking adaptations in a standardized format, GitHub fundamentally changed the way people interact with code. It created a shared grammar for the many programming languages housed in its nearly 14 million repositories. Now the open source, collaborative approach is starting to reshape how we organize materials, resources, and knowledge to make objects in our everyday lives. GitHub includes repositories for things like this taco recipe, which currently has 67 contributors. In answer to the Hack Dining challenge, the platform now has gitchen.org, a single place for cooking repositories—perhaps a precursor to the larger shift in home cooking Hesser and Stubbs propose.

Top chefs understand the potential of codifying cooking. Ferran Adriá closed his elBulli restaurant to launch the elBulli Foundation, which is creating BulliPedia—a shared archive of culinary knowledge that aims to stimulate creativity. Adriá believes that the cuisine of the past 50 years has evolved so much that it requires a new coding, a Cuisine Genome, to track flavor combinations, techniques, and technologies for cooking. Led by “the most influential chef of our time”, this top-down effort from gastronomy’s most brilliant minds combined with bottom-up sharing of recipes from home cooks represents a transformation in the ways we interact with culinary knowledge.

The signals of an open source, codified model extend beyond the kitchen to the entire food web. Learning from its own difficulty interpreting and complying with USDA standards, Wisconsin’s Underground Meats crowdfunded an open source guide to meat curing safety standards. Produced under a Creative Commons license, the guide will be modifiable by anyone, and will include instructional videos to share production processes.

The signals of an open source, codified model extend beyond the kitchen to the entire food web. Learning from its own difficulty interpreting and complying with USDA standards, Wisconsin’s Underground Meats crowdfunded an open source guide to meat curing safety standards. Produced under a Creative Commons license, the guide will be modifiable by anyone, and will include instructional videos to share production processes.

Imagine a universal grammar extended to check recipes against food safety compliance and regulation—a mashup between a cookbook and regulatory code. We could track the number of times someone builds on a process, discover gaps in regulation, or study ingredient nuances to assess local availability or cultural differences. Turning processes into a shared resource would reduce complexity, create new alliances throughout the supply chain, and build better feedback loops with regulators.

Another signal, the Open Source Seed Initiative, aims to build openness into the food system from the ground up. Packets of seed with a “free seed pledge” contain genetic resources that cannot be legally protected, creating a perpetual seed commons. If information about each seed was coded online and easily duplicated, tweaked, and reproduced for local conditions—and linked to repositories for processing and cooking methods—we would have a true seed-to-fork understanding of the processes by which we produce the food we eat.

“Eating is an agricultural act,” Wendell Berry reminds us, and it is increasingly just as much a technological act. The ways in which we engage with technology to grow, cook, and eat our food will undoubtedly change in the coming years. We have the opportunity to harness technology to create truly open, shared, and cherished knowledge and resources for our global food web.

Hacking Dining is an online conversation exploring how we might use technology and design to hack a better future for dining. Join the conversation between June 2 – July 30, and share your ideas in the comments, on Twitter using #hackdining, Facebook, LinkedIn or Tumblr.

________________

Rebecca Chesney is a communications and research manager with Institute for the Future, a Silicon Valley nonprofit foresight organization. She researches topics that range from the future of food security to augmentation of human sensory experiences. Rebecca is particularly interested in using food as a lens for exploring ways to reinvent the way we live, work, and connect with one another. As part of IFTF’s food futures team, she helps organizations and individuals take a long-term systems view of the tensions and possibilities for the global food web. Rebecca previously worked with the World Bank and wrote financial accounting standards for the United States. She is an award-winning food and travel photographer and a Certified Public Accountant, and she holds degrees in accounting and finance from Texas A&M University and an MA in the Anthropology of Food from SOAS, University of London.

Rebecca Chesney is a communications and research manager with Institute for the Future, a Silicon Valley nonprofit foresight organization. She researches topics that range from the future of food security to augmentation of human sensory experiences. Rebecca is particularly interested in using food as a lens for exploring ways to reinvent the way we live, work, and connect with one another. As part of IFTF’s food futures team, she helps organizations and individuals take a long-term systems view of the tensions and possibilities for the global food web. Rebecca previously worked with the World Bank and wrote financial accounting standards for the United States. She is an award-winning food and travel photographer and a Certified Public Accountant, and she holds degrees in accounting and finance from Texas A&M University and an MA in the Anthropology of Food from SOAS, University of London.