The quick answer is: don’t focus on the technology.

The quick answer is: don’t focus on the technology.

There have been not one, not two, but three papers published in the last six months, the last one published last week, encompassing an impressive body of work around behavior change and weight loss, from the same research group led by Bonnie Spring, PhD, at Northwestern University.

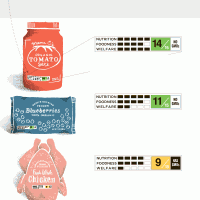

There’s a lot of stuff in here – everything from financial incentives to the way you coach people about behavior change to the use of mobile devices. If you don’t read them all (or don’t read any of them all the way through), it’s highly likely that you’ll come to the wrong conclusion, in my opinion, so I’m going to break it down here:

1. The way you counsel people about behavior change makes a difference

This is actually the most important part of the first two papers linked here, not the up to $730 incentive (more on that later). What the authors studied was competing theories about how to talk to people. They looked at four different ways, which I’m going to summarize, because it’s important – these are things that are cost-free and don’t require any capital expenditure to deploy .

- Theory 1: Familiarity hypothesis, I’ll call it “MOTS: More of the Same” – “Decrease your saturated fat intake, increase your physical activity”

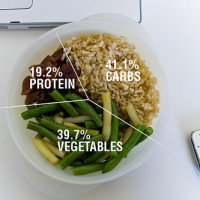

- Theory 2: Behavioral Economic hypothesis: Crowd out an unhealthy behavior with a heathy one – “Eat more fruits and vegetables, decrease your sedentary activity” < - This was the winner

- Theory 3: Low Inhibitory Demand, I’ll call it “Don’t be a downer, tell people what they CAN do rather than what they CAN’T” – “Eat more fruits and vegetables, increase physical activity”

People coached with the winning theory had significantly higher changes in a calculated “Diet-Activity” score compared to others. If you break it down a little more, it looks like it was far more likely that they could eat more fruits and veggies, than that they could increase their physical activity, across all groups. The winning group, though, dramatically decreased sedentary leisure, almost by half, which persisted 20 weeks later.

2. Paying people is a background activity to the above

In the first two papers, people were paid $175 to go through 3 weeks of intervention and point incentives along the way up to 20 weeks of follow up, for a total of $730. It seems like this got them through to recording their information. I don’t think it’s the most important feature of the study, and as the authors point out, probably not a realistic approach moving forward.

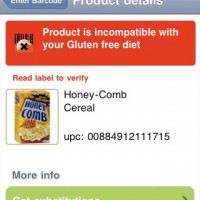

3. The mobile technology itself doesn’t help in isolation

Notice, I keep saying “mobile technology” not “smartphone.” That’s because these studies used PalmPilots (!) to support entry of data and target feedback. All of the study participants in the behavior change theory study improved their diet-activity score. There was no control group there, the goal was just to compare the theoretical approaches. The first study relied on self report of food intake and physical activity, which the authors sought to keep accurate by deploying a “bogus pipeline” approach where they told people to submit their grocery receipts and accelerometer data that were actually not used – clever.

The second study, which is in the third paper linked to this post, was more focused on weight loss itself rather than behavior change, and in it, the authors planned at the start that the mobile technology would be part of intensive coaching for all study subjects – they didn’t even try to have the mobile device make this happen for people. And in fact, the mobile device by itself didn’t make it happen for people – the one group who were randomized to get the mobile device and didn’t go to class actually gained weight. They gained more weight than the control group who had no mobile device.

What did happen for people was weight loss when they (a) used the mobile device to track and get feedback AND (b) they went to classes, in person. That was the requirement – that both happen, and when it did, this group lost more weight initially, and kept it off – average of 6.38 pounds at 12 months. The people with the mobile devices that didn’t go to classes, gained about 5 pounds at 12 months, which is more than the people who went to classes by themselves, and more than people who didn’t do the classes or get mobile devices.

There’s another really important piece of information in all of this, which is that the people who were randomized into the study were selected after a two week trial of recording their information. About 35% of the people that went into this gate didn’t make it, so in the end, this was a study of people who can use mobile devices to record their information.

As I said, there’s a lot here

I’m looking at this from a population/social determinants perspective, and I would ask the question, “Should mobile devices or apps be deployed to the entire population to make weight loss happen compared to other approaches?” The answer for me would be “no.”

I think what the authors are demonstrating is the answer to this question, “Should mobile devices or apps be deployed to people who are motivated to use apps to lose weight and participate in intensive behavioral interventions?” to which the answer is more of a “yes.”

Also, “Should we get smarter in communicating with people, with technology and not, about their choices?” – answer is “yes.”

I think we still need to think about technology as an enabler at the right time / place , everyone is necessary, and the hard work of looking at the causes of the causes of poor health is not going to go away (see: Now Reading: Why a focus on lifestyle behavior change may not improve health: The Marmot Review | Ted Eytan, MD).

The reason I love technology and have been invested in it for so long (and will continue to be) is because of its role in facilitating communication and connecting people to people. The best.app.ever is the human brain, the most important innovation in health information technology is listening. Oh, and prevention is the new HIT.

I communicated with Dr. Spring before writing this post to help me understand what we can take away from this research, which is very important/timely/useful (and I of course invited her to Washington, DC to the Behavior Change Summit in 2013 – More info on that here: Behavior Change: What can we learn from other industries? – EXAMPLES | Ted Eytan, MD). I learned a ton here that I didn’t know before, which makes me happy that talented behavioral scientists are working in this area.

This post originally appeared on Ted Eytan's blog.

-

Simona December 22, 2012 at 10:50 amInteresting post. I have not read the papers, so maybe the research already answers this question: do people maintain the weight loss? In other words: is the behavioral change observed during the study sustained after the study (and the $ incentive) ends?

-

@simo_Stardust March 23, 2013 at 3:16 pmDoes Mobile Technology Support Weight Loss and Behavior Change? http://t.co/Aj9zVcpKym via @foodtechconnect