Sponsoring challenges can be a great way for companies to discover new partners and products.

Sponsoring challenges can be a great way for companies to discover new partners and products.

Sanofi US’s Diabetes division is using them to reinvigorate its business model. Its first nationwide challenge, Data Design Diabetes 2011, was organized in six weeks, helped develop a way to use mobile phone data to measure how people are feeling — a potentially useful tool for the diabetes community — and earned it 19 million free media impressions. The winner of the 2012 challenge was announced this week: n4a Diabetes Care Center. It is a pretty quick pace for one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. It has been a cultural shift that took a lot of groundwork.

Challenges are a method of open innovation that is becoming relatively more common in highly regulated industries. They help a company harness the wisdom of a diverse group and take advantage of the principle of marginality, which essentially suggests that breakthroughs tend to come from people at the periphery of a field. InnoCentive, started by a former pharmaceutical executive, was founded in 2001 to help companies sponsor challenges and offer rewards to outsiders for solving their challenges. It is a method the Federal government also puts to work. In February 2011, President Obama’s Strategy for American Innovation reiterated the government’s commitment to “spurring innovation through prizes and challenges.” The Health Data Initiative was launched, in part, by Health and Human Services in 2010 to encourage innovators to use government data to address health issues. At its forum this June, companies like TopCoder, InnoCentive and Luminary Labs discussed best practices for running challenges on a panel titled Challengeology.

Getting an Innovation Challenge Off the Ground

A few years ago, Sanofi US began to look beyond the four walls of pharma and develop a strategy for broadening its products and services. A new position was created in its US Diabetes division, Head of Patient Solutions, to drive some of this process and Michele Polz, the former Senior Director of Innovation and New Customer Channels at Sanofi US, filled the role. She spent much of 2010 developing a strategy, with the support of senior leadership, for moving the diabetes division beyond drugs and into services. The key, which would later allow for Data Design Diabetes to happen in six weeks, was to first socialize the strategy internally and get her colleagues on board with the new direction.

“This meant, literally, shopping it around and having the internal meetings necessary,” says Polz. “We wanted to show big pharma can innovate.”

After all, it is the kind of big company where some people joke about it taking them four weeks to get a phone, Polz says humorously. Her partner in crime for developing and implementing the new strategy was Sara Holoubek, founder of innovation consulting firm Luminary Labs.

In the early days, Polz and Holoubek had a slide deck for those meetings to explain what Sanofi US Diabetes was proposing. They found it was critical to approach internal stakeholders (i.e., senior staff in the legal, regulatory, and marketing departments) in the right way — by making it clear that the Patient Solutions team wanted to solve the problem collectively. Polz and Holoubek found that message really resonated with other employees, even those outside the US Diabetes Division.

That was the foundation. Then in March 2011, at SXSW, Holoubek spoke with Aman Bhandari, now Senior Advisor to the CTO of the United States, who recommended looking into challenges as a way to find the right external partners. “We were looking for a pipeline to introduce the company to innovators and innovators to Sanofi US,” says Holoubek.

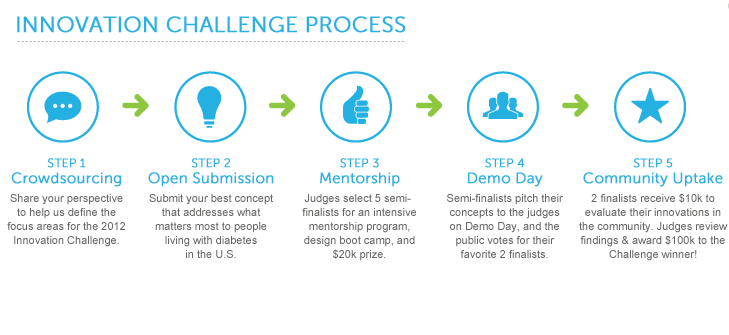

About six weeks later, the first Sanofi US Data Design Diabetes challenge was up and running, offering $100,000 and a one month residency at the Rock Health incubator in San Francisco to the winner. Staff were already familiar with the concept and how it fit into US Diabetes’ overall goal and strategy so the legal, regulatory and marketing pathways were clear. Sanofi US received 100 entries and an independent panel of judges narrowed them down to five and then two and then one.

“We’ve seen great work and ideas that have come out of the Data Design Diabetes challenge,” says Bhandari. “This challenge is part of our broader effort to get outside thinking and solutions to our health care problems. By stimulating new ways of thinking, problem solving and collaborating….”

Challenge Results

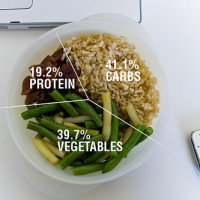

The winner of that 2011 challenge was Ginger.io, a platform that analyzes mobile phone data to determine the mood of its owner, relying on data points like how often they are making phone calls or texting. In the case of diabetes, people with the disease can be prone to depression and using the phone as an early warning system could help a company like Sanofi US tailor an offering or intervention that helps people better manage their physical and mental health. Ginger.io went on to raise $1.7 million in venture funding and although Sanofi US and Ginger.io do not have a formal partnership, they are discussing the potential for future collaboration.

Sanofi US does not own the intellectual property of the finalists in their challenges and for some companies this can be a sticking point. “Most large corporations are afraid of [not owning the IP], but if you help someone along the way, you’re going to be the first to have the chance to partner with them,” says Holoubek. At the Challengeology panel in D.C. a similar point was made. Dwayne Spradlin, the President and CEO of InnoCentive, noted that the prize purse would have to be in the millions if the company wants to own the IP outright and it is not necessarily a better route.

The benefits to a company of running a challenge go beyond just testing a solution to a problem or a new product. “There’s an opportunity to create an incredible halo effect,” says Holoubek. She said for the first Data Design Diabetes challenge they had “zero media spend” but 19 million monthly media impressions because of the interest in what Sanofi US was doing.

The 2012 challenge winner was announced earlier this week: n4a Diabetes Care Center. Using data, it is developing a way to target diabetics that are not properly managing their condition in order to stage interventions that might prevent hospitalizations.

“We’re doing things [in months] that in the past would have taken 4-5 years to develop at ten times the cost,” says Polz. “We’re doing some cool things,” and redefining the company in the process.