From January 7 – February 8, Food+Tech Connect and The Future Market are hosting Biodiversity: The Intersection of Taste & Sustainability, an editorial series featuring interviews with over 45 leading food industry CEOs, executives, farmers, investors and researchers on the role of biodiversity in the food industry. See the full list of participants and read about why biodiversity in food is important here.

Around the globe, cultivation of local crops is increasingly being lost to the monocropping of non-native commercial ones. Yolélé Foods wants to change this by creating market demand for traditional West African crops. Its first product is fonio, a West African ancient grain that is highly nutritious, featuring high amounts of amino acids like methionine and cysteine. Fonio is also one of the fastest growing crops on the planet — maturing in as little as 8 weeks — and can thrive in poor soil and with limited water. A cross between couscous and quinoa, restaurants like Tender Greens are already putting the grain on its menu.

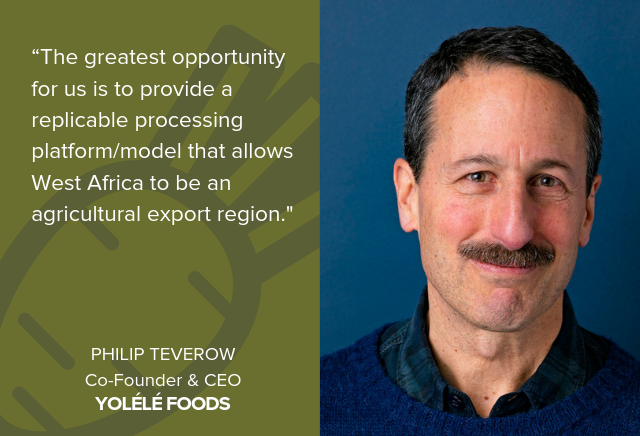

Below, co-founder and CEO Philp Teverow talks to me about how the company is working with farmers and creating a processing and distribution platform that will help West Africa become an agricultural export region.

_____________________

Danielle Gould: Is biodiversity a priority for Yolélé Foods? If so, how and why?

Philip Teverow: Biodiversity is at the core of our business. Climate change is making it harder to subsist for the 80 percent of West Africans who make their living from farming. One reason is a reliance on non-native commercial crops that have been imposed on the region, like cotton and maize, which tend to come with a monocrop approach. We believe that the region can be an agricultural export powerhouse and regain food sovereignty by focusing on traditional crops like fonio, the ancient African grain that is our initial ingredient platform.

DG: How does Yolélé define and think about biodiversity? What does an ideal biodiverse food system look like?

PT: For us biodiversity means a wide variety of species, adapted to different conditions. We think that the arid Sahel region of Africa would be highly productive if its agricultural systems took into account current and projected meteorological conditions, and the human capital that is so abundant there. In West Africa, capital is not available, and there are tons of people trying to make a living in agriculture. Monocropping might make financial sense for individual farmers in any given year, but it’s not an option for smallholders farming by hand, often without even draft animals. The only system that can work in those conditions is one that uses rotation and intercropping of well adapted local crops that work in concert with one another in the absence of chemicals and technology. A good level of biodiversity is the one that can yield enough to live on and also generate cash to spend on quality of life improvements, year after year, while enriching the soil to make it even more productive in the long run.

DG: What is Yolélé doing or planning to do to promote biodiversity?

PT: First of all, we’re creating demand for traditional crops so that it makes financial sense for farmers to devote more acreage to them than they would without the prospect of making money. Second, we are building processing capacity, the absence of which has prevented these crops from having commercial viability until now.

DG: What is the business case for products that promote a more biodiverse food system?

PT: That’s a tough one! The business case requires a long view – what kind of systems can keep on providing results beyond the next few quarters or years? What kind of systems can work for the next generation, when climate change’s effects mean today’s practices will no longer apply? For us, the business case relies on people who choose to spend their grocery dollars on products they see as contributing to a solution rather than those contributing to the problem.

DG: What investments need to be made to create a more biodiverse food system?

PT: Market building (education, product development, sales, promotion) and processing capacity. In West Africa, infrastructure for efficient logistics.

DG: What are the greatest challenges and opportunities your organization faces for creating a more biodiverse system? What are you doing to overcome or capture them?

PT: Challenges include agricultural productivity, processing performance and nutritional strength of ancestral species; processing capacity and efficiency of those species; capital to address those issues. We are engaging in crop trials to improve the crops; partnering with food processors and food processing equipment manufacturers to build efficient, scalable systems; and raising capital to pay for those activities.

The greatest opportunity for us is to provide a replicable processing platform/model that allows West Africa to be an agricultural export region.

DG: What are some of the most important things retailers, food manufacturers and other key parts of the food supply chain can do to support biodiversity?

PT: How about a Biodiverse tag on the self, just like gluten-free? How about a group of manufacturers getting together on a campaign to explain in very simply terms the importance of consumer choices around biodiversity? How about distributor-led Biodiverse sets?

DG: If we get to a perfectly biodiverse food system, how would that change the typical selection of products we see in a grocery store?

PT: My first thought was that there would be whole lot less wheat, rice and maize. But that’s not really so. There’s plenty of room for biodiversity within each of those crops. It’s really complicated in the baking industry, whose equipment and processes have been built around flour with specific performance parameters provided only by a few strains of wheat. But we’re nothing if not ingenious as a species. I think we can come up with efficient ways to adjust formulas and processes to accommodate varying degrees of protein.

DG: Are there certain products you would like to see more of in the food industry — either in foodservice or CPG — that would help promote a more biodiverse agricultural system?

PT: Fonio!!!!

DG: What is your vision for what a more biodiverse food system looks like in 10-15 years?

PT: The aerial view over Africa’s Sahel region today it looks brown. We want that view to be a patchwork of green fields growing multiple crops for local consumption and for cash for a better life.

Read all of the interviews here and learn more about Biodiversity at The Future Market.

________________________

Philip Teverow , co-founder & CEO of Yolélé

Philip Teverow , co-founder & CEO of Yolélé

Philip Teverow is the co-founder & CEO of Yolélé, a revolutionary African food brand that is building a vertically integrated supply chain for traditional African crops, focusing initially on the ancient grain fonio. He has been developing and launching natural and specialty food brands and products across multiple categories for decades, including 13 years at Dean & Deluca, where he imported quinoa to the US in 1980’s.