From January 7-31, Food+Tech Connect and The Future Market are hosting Biodiversity: The Intersection of Taste & Sustainability, an editorial series featuring interviews with over 45 leading food industry CEOs, executives, farmers, investors and researchers on the role of biodiversity in the food industry. See the full list of participants and read about why biodiversity in food is important here.

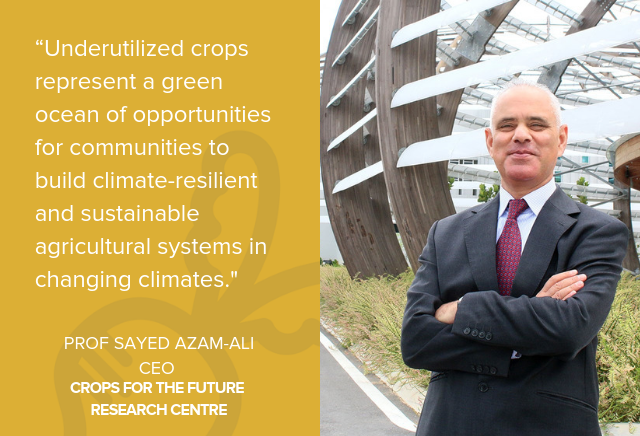

Below, we speak with Prof Sayed Azam-Ali, CEO of Crops For the Future Research Centre (CFFRC), about CFFRC’s research and promotion of underutilized crops that are climate-resilient, nutritious and economically viable. One of the ways CFFRC is promoting the utilization of ‘forgotten foods’ is through the Forgotten Foods Network , an initiative launched in 2017 by HRH The Prince of Wales, which is dedicated to collecting and sharing information on foods, recipes and traditions. Azam-Ali argues that climate change and dietary diversity are our two of our biggest challenges, and that we need more investment in eduction and scientific research to promote underutilized crops.

________________________

Danielle Gould: How does CFFRC define and think about biodiversity?

Prof Sayed Azam-Ali: Crops For the Future Research Centre (CFFRC) is the world’s first and only centre dedicated solely to research on underutilized crops that can contribute to humanity’s and the planet’s needs in an era of climate change. CFFRC has the mandate, facilities and expertise to evaluate underutilized crops that can diversify agricultural value chains with climate-resilient, nutritious and economically viable options to deliver climate resilient nutrition.

At CFFRC, we look at agricultural diversification beyond only major commodity crops. So called ‘underutilized’ crops represent a green ocean of opportunities for communities to build climate-resilient and sustainable agricultural systems in changing climates. Agricultural diversification also offers an opportunity for us to diversify the food we eat, beyond just options for our sustenance but also for our nourishment.

DG: What is CFFRC doing or planning to do to promote biodiversity?

SAA: There are thousands of underutilized and ‘forgotten foods’ that are being increasingly displaced by modern, uniform and processed foods. Forgotten foods include ingredients from neglected crops, animals, vegetables and even insects, as well as traditional varieties of the major staple crops. These forgotten foods deserve to be evaluated to explore which can nourish future generations. We need to explore the diverse basket that were the foods of our ancestors; foods that used to be part of the diet of past generations but which have been neglected and forgotten by modern societies.

One of the ways we are doing this is through CFFRC’s Forgotten Foods Network (FFN), an initiative which was launched on November 3, 2017 by HRH The Prince of Wales at the CFFRC headquarters in Malaysia. FFN is a global initiative that collects and shares information on foods, recipes and traditions that are part of our common heritage. By creating this network, we hope to discover and share foods that can transform the way we eat now and nourish us in climates of the future.

DG: What does an ideal biodiverse food system look like? How do you measure biodiversity, and when will we know when we’ve arrived at a “good” level of biodiversity?

SAA: An ideal food system should integrate a systematic, evidence-based approach as each value chain includes many stakeholders with diverse interests and capabilities. We need innovations along the whole food value chain to provide economically viable and climate-resilient options that can `transform agriculture for good’.

Nine billion people, on a hotter planet with scarce water and energy represent the `Perfect Storm’ for humanity. By 2050, demand for food and animal feed will at least double. At the same time, water resources are diminishing, arable land is being degraded and rural populations are moving to cities. Food and nutritional insecurity and climate change will disproportionately affect many countries that are prone to rising sea levels, adverse weather and fragile infrastructure. By itself, conventional agriculture – the intensive production of major crops on good soils – will not meet humanity’s needs without using more resources than the planet can afford. In hotter, volatile climates with billions more to feed, `business as usual’ is not an option.

Feeding a growing population on a hotter planet requires a new vision of agriculture. Rather than being its major cause, agriculture can become humanity’s greatest ally against climate change. This means diversifying agricultural value chains with `climate-resilient’ crops that can produce marketable products without the need for carbon-heavy production systems and supply chains.

DG: How would you describe the current state of biodiversity? What are the key forces that are helping or hurting biodiversity today?

SAA: Our dependence on a few major crops to feed humanity risks global food and nutritional insecurity. Only four staple crops – wheat, rice, maize and potatoes – now provide over 60 percent of global calories and only 30 crops constitute over 95 percent of the global diet. Current agricultural practices of intensive farming and long commodity supply chains are major contributors to climate change and global CO2 emissions. We need to diversify agricultural value chains with climate-resilient, nutritious and economically viable options if we are to nourish a growing population on a hotter planet and deliver `climate-resilient nutrition’.

We need to be more creative and be less reliant on only major crops if we wish to increase the diversity and quality of our diets. This requires novel research to evaluate the dietary potential of less common, local or underutilized plants – grains, cereals, leaves, fruits, vegetables – many of which contain relatively high levels of vitamins, minerals and phytochemicals.

DG: What’s at stake for our society if biodiversity is reduced? Are there examples where a lack of biodiversity has caused problems within an ecosystem or community?

SAA: Most of the plant-based food consumed globally depends on a few major ‘staple’ crops. If any of these fail, global food security is at risk. Nutritional security is dependent on the quality rather than quantity of food consumed. Mounting evidence shows a strong correlation between the increasing levels of CO2 in the atmosphere and decreasing nutrient and micronutrient content of staple crops. Alarmingly studies show that staple crops contain less zinc, iron and protein when grown at elevated CO2 levels.

The declining diversity of modern agricultural systems towards intensively farmed monocultures of only a few crops has reduced the supply of foods from which we can make dietary choices. This decline has profound implications on our health, particularly that of young children, who, without a proper diet, cannot meet their nutritional and energy needs.

DG: What is the scientific and/or business case for a biodiverse food system?

SAA: It is clear that to provide food and nutritional security for an estimated 8.5 billion people by 2030, in an increasingly hot and riskier world, we can no longer rely solely on a few staple crops. Attention should be shifted towards policies and food systems that support the quality and diversity of food, as well as its quantity and calorific content. However, much of the literature on the potential health benefits of consuming a diverse diet that includes underutilized plant foods is anecdotal rather than evidence based. To provide a credible evidence-base, a concerted research effort and investment in these neglected and under-researched species is much needed. For underutilized species to play a more significant role in dietary diversification and nutritional security, it is essential to include capacity building for all stakeholders involved in the value chains from growers through to markets.

DG: What investments need to be made to create a more biodiverse food system?

SAA: Consumers are increasingly interested in more nutritious and safe foods. However, ‘dietary diversification’ requires scientific evidence, new technologies and business skills to develop value chains that can diversify diets now and in future climates. Unlike major crops, little investment has been committed to any underutilized crops to understand its economic value, behavior in changing climates and potential products. In the marketplace, there are gaps in the supply chain and limited information on promising crops, their potential uses, nutritional value and processes involved in taking them from farm to plate. Although underutilized species have long been overlooked, interest is growing in their potential to contribute to food and nutritional security and improved livelihood options. It is crucial that we invest in more awareness and scientific research on underutilized crops that can provide us sustenance and nourishment in an era of climate change.

DG: How might we reinvent capital structures or create incentives to increase investment in biodiversity?

In September 2015, most countries and international agencies made commitments to the 2030 United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development which has 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In December 2015, alongside the UNFCCC Paris Climate Meeting, CFFRC and its partners proposed an ambitious ‘Global Action Plan for Agricultural Diversification’ (GAPAD) to address specific SDGs through agricultural diversification beyond only the world’s major crops. The target SDGs of GAPAD include SDG2 (Zero Hunger) SDG7 (Energy), SDG12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG13 (Climate Action) and SDG15 (Life on Land). Each of these SDGs has a direct relationship with biodiversity and will require significant capital investments if it is be achieved in the next decade.

DG: What are some of the most important things food manufacturers, chefs, retailers, farmers, and other key parts of the supply chain can do to support biodiversity?

SAA: Manufacturers, chefs, retailers and farmers all have a big role to play in promoting biodiversity. Ideally, supporting and incorporating the use of underutilized species into restaurant menus and supermarkets will help garner more attention towards biodiversity as novel sources of food and nutrition.

DG: Where can eaters and food industry professionals go to learn more about biodiversity issues and what they can do to help?

SAA: We believe that there are thousands of forgotten foods that can help make our diets more interesting, more nutritious and more sustainable. There is growing interest both in the food that we eat and the sustainable sourcing of the ingredients from which it is produced. CFFRC is working with its partners to bring knowledge about `Forgotten Foods’ into the public space. If we can rediscover recipes from these crops, we can diversify our diets now and in future climates.

How can we rediscover our lost foods and their recipes? Knowledge about these foods, their ingredients and methods of preparation, is often in the heads of older people; our parents, grandparents and great grandparents. We must rediscover these recipes and the knowledge that goes with them and share it with younger generations. By finding our forgotten foods, we can identify which crops could help feed the future.

DG: Are there certifications or other signals that can help the average consumer determine what kinds of foods are helping promote biodiversity?

SAA: Whilst there are many social media tools that describe recipes and cuisines from around the world, there are very few applications that identify the diversity of ingredients and their sustainability in the face of climate change and use of natural resources. CFFRC is developing a social media app that links food with their nutritional value and environmental footprint. Through this app, we hope to actively advise consumers on their food habits, while expanding the existing database on global foods and eating habits. The app examines how to define parameters for valuing the health and nutritional benefits of food, as well as its impact on environmental sustainability, as a societal decision.

DG: What are examples of food products that promote biodiversity?

SAA: At CFFRC, we develop a lot of new products that reinvent ‘traditional’ foods with a modern twist, by using novel ingredients from underutilized crops. Snacks like biscotti and `murukku’ are revamped by our food technologists to include ingredients from protein-packed legumes like bambara groundnut. We are also developing vegetarian bambara burger patties and moringa pesto for new markets. We can show that foods from underutilized crops can be delicious, novel and climate-smart.

DG: What, if any, exciting products, technologies or services are you seeing that support a more biodiverse food system?

Public awareness and education campaigns can effectively encourage informed decision-making by the public. Through initiatives such as the annual EAT Forum and Lexicon’s Rediscovered Food Initiative, we are starting to see more engagement on biodiversity as an important catalyst to sustaining our food systems and environment in the face of changing climates.

DG: Are there certain products you would like to see more of in the food industry — either in foodservice or CPG — that would help promote a more biodiverse agricultural system?

SAA: Yes, the sorts of apps that we are developing that link recipes, nutrition and environment together. We often view food, nutrition, environment and climate as separate entities, when in fact, if we do not care for one, then the others will be severely affected. It is important to acknowledge that link as a small and progressive step towards building a more sustainable future for generations to come.

DG: What is your vision for what a more biodiverse food system looks like in 10-15 years?

SAA: Until now, our current food system has successfully fed a growing global population of over 7 billion people. The question is whether it can nourish over 9 billion people on a hotter planet without destroying the natural resources on which we all depend. In an era of societal, political and climatic changes we need new ideas that harness the huge potential of biodiversity to feed, nourish and support humanity. Our future will depend on the diversity of our food systems, the landscapes from they derive and the innovation and skill sets of those who bring them to us.

DG: Anything else you want to share?

The twin challenges of climate change and dietary diversity require urgent, imaginative and common actions. Neither will `better-business-as-usual’ nor technological solutions be enough by themselves. They require a new paradigm for agriculture that seeks to deliver climate-resilience skill sets and better nutrition to communities across the world. In short, we need to put `climate-resilient nutrition’ at the heart of our agrifood systems. The attached CFFRC Policy Brief provides more detail on this concept.

Read all of the interviews here and learn more about Biodiversity at The Future Market.

______________________

Prof. Sayed Azam-Ali, CEO of Crops For the Future

Prof. Sayed Azam-Ali, CEO of Crops For the Future

Prof. Sayed Azam-Ali was appointed as the first Chief Executive Officer of Crops For the Future (CFF) in August 2011. In 2017, he was elected as Chair of the Association of International Research and Development Centers for Agriculture (AIRCA), a nine-member alliance focussed on increasing global food security by supporting smallholder agriculture within healthy sustainable and climate-smart landscapes. Prof Azam-Ali also holds the Chair in Global Food Security at the University of Nottingham.

After his first degree in Plant Biology at the University of Wales, Prof. Azam-Ali completed his PhD in Environmental Physics at the University of Nottingham in 1983. He then worked as a plant physiologist at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), India, before returning to Nottingham where he became Professor of Tropical Agronomy in 2006. At Nottingham, Prof. Azam-Ali coordinated three major EU-funded Programmes on bambara groundnut and was a principal partner in two other EU programmes. He was also Principal Investigator for six UK DFiD projects. In 2008, Prof. Azam-Ali was appointed as Vice-Provost (Research and Internationalisation) at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, where he successfully secured the EU funded MYEULINK programme that links major research universities in Malaysia with counterparts in Europe. He also coordinated the successful bid by the University of Nottingham to co-host CFF against stiff international competition. Prof. Azam-Ali was instrumental in the establishment of CFF as the world’s first centre dedicated to research on underutilised crops for food and non-food uses.