Commodities markets and anyone in the food supply chain rely on USDA data to operate. This includes critical data that farmers depend on to price crops and livestock, as well as determine which commodities to grow and when to sell them. But since the government shutdown began on October 1, the USDA has ceased publishing all data, and its shuttered its website making all historical reports inaccessible.

There are some private data providers, like Informa Economics and Pro Exporter, that provide market quotes, but they are expensive – average of $8,000 per subscription – and its not nearly as comprehensive as the USDA data,Thomas Sleight, president of The U.S. Grains Council, tells Reuters.

Now, there’s a new solution that’s more affordable, and, unlike others, is designed for the organic and non-GMO supply chain. Last week, Mercaris, a market data service and online trading platform for organic, non-GMO and certified agricultural commodities, launched its first Data Service Report and announced Whole Foods as its first customer.

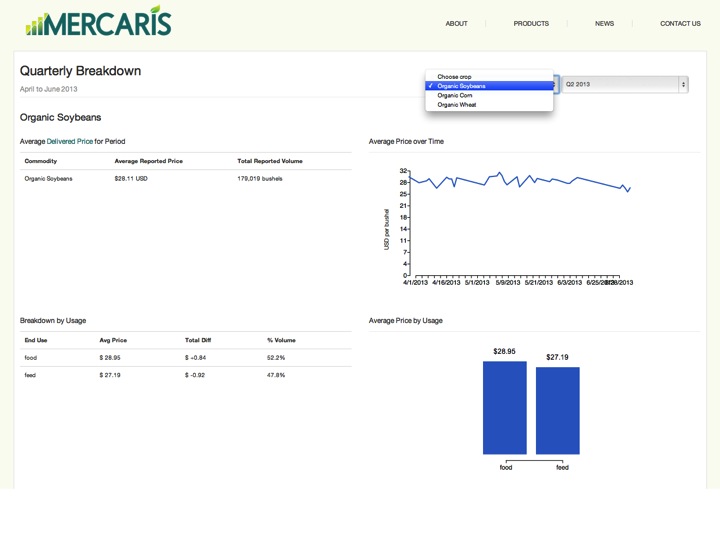

The platform offers monthly or yearly subscription to a variety of reports designed to help producers, elevators, mills, manufacturers and retailers know how much they should be charge or pay for products. The report tracks and compares spot and forward prices of organic corn, organic soybean and organic wheat markets – from the point of first delivery – across the US and Canada. It also tracks monthly US export statistics. The trading platform, launching in November, will allow buyers and sellers to trade commodities online.

As a result of the shutdown, the bi-weekly price report on organic grain & feedstuffs is not unavailable. So this past Monday, Mercaris launched a weekly price report from its proprietary, ongoing market price survey.

In addition to the reports, subscribers can also use the platform to access information, like average prices, food prices vs. feed prices and historical pricing data. Subscribers can buy data for a single crop, like corn, for $80 per month, or you an buy data for all three crops for $230/month. In the near future, it will be roll out other crops like non-GMO soybeans, non-GMO corn and coffee. For the trading platform, it will initially charge a transaction fee that’s 2% of the value of the trade. Eventually it may also charge a membership fee.

Founded by Kellee James, formerly an economist at Chicago Climate Exchange and a White House fellow, Mercaris is an ambitious and important undertaking. In 2011, the organics sector grew to a $29.2 billion industry, but it’s plagued with insufficient data for decision making. Armed with an $800,000 seed round from investors like Ulupono Initiative of the Omidyar Group, Kapor Capital and Joanne Wilson, James and her team of two are on their way to changing that.

I spoke with James to learn more about Mercaris, its data collection and business model. Read our edited interview below.

Danielle Gould: Who is your typical customer?

Kellee James: It looks like a snapshot of the organic sector itself. Organics has evolved. Maybe if we had been talking about this ten years ago maybe it would have been mostly small or family-owned mom and pop type of outfits. Now there are still those folks in the sector, but [you] also have General Mills, Coca-Cola, Hershey’s, and things like that. Our customers will come from each of those segments, but the one thing I think our customers have in common regardless of size is that their balance sheets are exposed to fluctuating commodity prices. And the price of the raw material matters to them.

DG: What’s the size of this market?

KJ: We don’t know the total number yet. That’s more of the science of the data is not where it should be for the sector, but we could look at some big numbers. USDA has certified for the US last year 17,750 organizations that have organic jurisdiction(?). Now that’s everything from farms to food processors to manufacturers – anyone who can get an organic certification. Some subset of those handle specific crops – grains, vegetables, fruit. Now keep in mind you don’t have to be a certified organization, for example there are brokers that never take possession or delivery of organic grains. They can still deal in organic grains and not necessarily be certified by the USDA. So the universe of businesses involved in organics is much bigger than 17k.

DG: How are people currently determining market prices and trading organic, non-GMO and certified agricultural commodities?

KJ: Transaction costs are very high in the sector. A producer, for example, might not be able to get good crop insurance to be fairly compensated in the event of crop loss, so there is a transaction cost there that they are just simply absorbing. For a food manufacturer, they may not have good data on supply and demand, a proxy for the supply and demand curve, so they may have to keep more inventory on demand to try and protect against that. These are all costs that are built into the system and that’s what we’re trying to solve for. To find out prices they call around – get on the phone to literally call as many people as they can to find out what’s going on in the market.

DG: Who participants in your surveys?

KJ: Our survey participants are all first handlers of grain, so they’re mills and elevators for the most part. There are a few brokers in there, but they are all working directly with growers. There are about 40 of them across the US and 2 provinces in Canada. In 3 months, we’ve collected 2 million bushels worth of grain trades across the 3 different grains. What that means percentage wise – we know from USDA stats how much acreage and grains are produced across the US – [is that] we’re collecting between 2-4 percent of the total volume grown in the US. Now, the market is bigger than that because we import a lot of grains, but for domestic production we’re collecting quite a bit.

DG: What’s the incentive for them to share their data?

KJ: A lot of them are doing it because they understand that this is good for the industry – they see this as beneficial and worth participating in. The commercial logic is they get data for free. If they’re part of the survey, then we don’t charge them for the data reports. If they’re reporting on organic corn then they get organic corn prices free of charge.

DG: How do you ensure data integrity?

KJ: One is the software itself. We have algorithms that look for strange prices – things that fall outside the norms for price or volume – and we can flag those to do research to check if they’re good. We also have the ability to match opposite sides of trades. If you’re reporting in as a buyer we can find the seller to make sure the prices match. We have the ability to do this, but we’re not necessarily always doing it right now. The other thing is we are asking people to report actual trades [rather than what you would pay for something].

DG: How does the technology work?

KJ: The technology for the data service side is nothing new. For a variety of industries, lots of people follow prices of raw materials. The old fashioned way of doing it [would be] an analyst that covered a sector getting on the phone, calling around and then publishing their observation. We use technology to cut down on the cost and hopefully maintain accuracy. Instead of calling around, our survey participants log in to their own homepage on our website, and they upload their data directly into our website. It also cuts down on human error. We’ve had that up and running for about three months now. On the trading platform side we’re still building. It’s a matching engine and user interface to handle order entry and order matching.

DG: Will this data shift the market and increase production of organic and non-GMO foods?

KJ: The sort of economic underpinning of this is that by providing the prices and showing that there’s a premium out there that it will encourage the market to produce more of it.