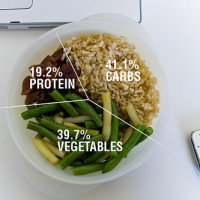

Photo Credit: Erich Ferdinand

You can pay your farmer, or you can pay your doctor.” Arguably the most memorable line from 12-year-old sustainable food advocate Birke Baehr’s TEDx talk, these words of wisdom hit home. You can either choose whole foods grown sustainably, or you can suffer the consequences of a diet full of processed food, which often lead to the doctor’s office. And doctors, even more than the rest of us, are major targets of pharmaceutical companies, representatives of which aggressively court them into prescribing their drugs to you.

The impacts of industrial agriculture are a regular topic of discussion on Ecocentric, but we’ve never delved into the complex relationship between Big Ag and Big Pharma, so we decided to take a look. Here is a roundup of some of the alarming connections between our drug industry and our food industry:

GE Salmon: Drug or Food Additive?

AquaBounty’s “AquAdvantage” genetically engineered salmon, aka “Frankenfish,” appears to be steadily swimming towards approval despite concerns regarding its potential environmental consequences, its effects on human health and the integrity (or lackthereof) of studies that claim it is safe. The FDA has ruled that it will evaluate GE salmon as an animal drug and not a food additive, a move many consumer groups criticize (since the salmon will obviously be marketed as a food product). (Aquabounty submitted an application to FDA for approval of the GE salmon under the new animal drug provisions of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which makes it easier for pharmaceutical companies to get new drugs approved). Currently, the FDA is going on data provided by AquaBounty and even their own studies admit that GE salmon may contain increased levels of carcinogenic hormones.

In February, Food & Water Watch, Consumers Union and the Center for Food Safety submitted a formal petition asking the FDA to classify GE salmon and all of its components as a food additive, which would ensure a more rigorous review process. This would require GE salmon to undergo comprehensive toxicological studies required of any novel substance added to food and would ensure that foods entering the market are safe to consume and are properly labeled.

Paula Deen: Diabetic and Big Pharma Saleswoman

When fried food guru Paula Deen, who once used doughnuts as buns for her bacon-egg burgers, announced she had type-2 diabetes earlier this year, it wasn’t exactly a shocker. It was, however, a pivotal moment in the career of the famous TV chef, who’d kept her disease hidden for several years. With the announcement, Deen had the opportunity to help her legions of fans learn from her mistakes and educate the public on the importance of healthy eating. Instead, she insisted she had always practiced moderation and announced she was partnering with drug maker Novo Nordisk to promote a new Type 2 Diabetes drug called Victoza, which costs $500 a month and Deen proudly admits she injects daily. By the way, side-effects of Victoza may include pancreatitis and thyroid cancer. In recent months, Deen has talked more about diet and exercise changes.

Eli Lilly: Maker of rGBH and Breast Cancer Drugs

In 2007, consumer pressure brought by groups like Food & Water Watch and the Organic Consumers Association lead retailers of dairy products – first Starbucks, then supermarket chains like Safeway and eventually Walmart – to eliminate dairy from cows treated with recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH) from their supply chain. Developed and manufactured by Monsanto under the product name Posilac, this genetically engineered hormone artificially increases milk production by 10 to 15 percent, but not without side effects, most notably mastitis (painful udder infections that lead to increased white blood cells – aka pus – in milk). Over the years, a number of studies have linked rBGH to breast cancer. The Starbucks decision and resultant domino effect left the industry reeling and in August 2008, Monsanto sold their Posilac division to Eli Lilly and Company for $300 million. Here’s where things get shadier: Eli Lilly simultaneously markets Gemzar, a drug used to treat breast cancer and Evista, a drug used to reduce risk of the disease. According to Breast Cancer Action’s (BCA) Stop Milking Cancer campaign, “Eli Lilly has created a highly lucrative profit cycle that contributes to increased risk of breast cancer, aims to prevent it, and treats it.”

Eli Lilly: Also Causing and Treating Diabetes!

Apparently, this company is not one to shy away from controversy. Over the past decade, Eli Lilly has also seen one of its best-selling drugs, a schizophrenia medication called Zyprexa, cost the company over $1 billion in class action lawsuits, after covering up its links to obesity, increased blood sugar and resultant diabetes. Patients prescribed the drug experienced massive weight gain (as much as 100 pounds in some cases) and the company was shown to have covered up its knowledge of the side effect. The company has since partnered with a company called Boehringer Ingelheim on a diabetes medication and regained its footing in the global market, even earning a ranking in the Research Institute’s most recent list of 100 most reputable companies.

Livestock Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance

Almost seventy percent of all antibiotics sold in the US are used on healthy livestock to promote faster weight gain and compensate for unsanitary and overcrowded conditions. In 1975 an average steer sent to slaughter weighed 1,000 pounds, as opposed to the 1,300 pound average of today. This is because of antibiotics, hormones and other growth-enhancing drugs, which makes the industrial agriculture an enormous, vital (please forgive the pun) cash cow for the pharmaceutical industry.

The unnecessary use of massive quantities of antibiotics on healthy livestock has led to a rise in antibiotic resistant bacteria known as “superbugs” that reduce the effectiveness of life-saving antibiotics for humans. Antibiotic resistance can lead to extended illnesses, greater side effects of antibiotic use and death when these treatments fail entirely. This public health threat is not merely the result of an accidental, systematic overdose. As a result as an investigation by the FDA, it has been common knowledge (at least for industry) since the 1970s that dosing healthy livestock with antibiotics like penicillin and tetracyclines poses a risk to human health. However, due to the lobbying power of the two industries, the FDA never did anything about it—even as they acknowledged the danger these drugs posed.

A 2003 report edited by the current Commissioner of the FDA said that if nothing is done to address the causes of antibiotic resistance, including the overuse of antibiotics in livestock, the “specter of untreatable infections — a regression to the pre-antibiotic era — is looming just around the corner.” Last May, the NRDC led a lawsuit against the FDA forcing them to act — and won. But instead of enforcing real regulations, the agency issued voluntary “guidelines” for the industry — hardly the kind of action to prevent that ‘spector of untreatable infections.’ Back in March a district court in Manhattan ordered the FDA to consider two citizen petitions requesting that the agency revisit its decision not to ban some other antibiotics in animal feed. The court has ruled that the FDA’s decision was “arbitrary and capricious” and criticized the agency for relying on industry to voluntarily limit the use of these drugs. The 40-year fight over antibiotics is far from over, it would seem. Most recently, a consumer campaign launched by the Consumers Union and FixFood has targeted grocery stores around the country, pressuring them to sell more meat raised without the use of subtherapeutic antibiotics. Read more and take action here.

And…in Ethanol

Antibiotics are also sneaking into livestock via ethanol production, despite federal regulations to the contrary. Antibiotics are widely used in ethanol production to curb bacteria outbreaks, despite the fact that there are other viable alternatives. (Effective, cost-competitive antimicrobial alternatives are readily available to producers and many have begun to use them.) The leftover corn mash from the ethanol production process known as “distillers grains” is repurposed and sold as livestock feed to cattle, dairy, swine and poultry producers — and the antibiotics used during the ethanol production process come along for the ride. For more information about ethanol and antibiotic resistance, see The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy’s comprehensive report, Bugs in the System: How the FDA Fails to Regulate Antibiotics in Ethanol Production.

Big Pharma and Higher Ed

Over the past few decades, public funding for agriculture research has tapered off and instead has been replaced with billions of dollars in grants every year by private interests, including pharmaceutical companies. Federal R&D funds for ag research has leveled off at about $5 billion a year, while private funding rose steadily and is now at approximately $6 billion. This is obviously bad for a number of reasons, not least of which is the conflict of interest created when pharmaceutical companies fund research on their own products. This leaves the unbiased research up to consumer groups and other researchers who aren’t as well funded. About a month ago an excellent article was published in the Chronicle of Higher Education documenting how university animal-health research is now dominated by the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical giants reach out (read: pay) to professors at public land-grant universities, who then not only act as paid researchers to develop new products but also as salespeople who then help market said products directly to cattle feedlot operators. Land-grant universities were originally established to best serve our country’s agricultural needs, but this trend of private investment has impacted scientific integrity across the country.

As the debate over the impacts of our eating habits rages on, so too does the debate over our health care system and as we’ve seen here, the two are linked in ways that go far beyond Birke’s wise observation. Can an apple a day keep the doctor away? Maybe not forever, but to say the least, we’d like to see more up-front discussion of the links between diet and disease and less behind-the-scenes collusion between Big Ag and Big Pharma.

This post originally appeared on Ecocentric.

![[Infographic of the Week] Superbugs: From Farm To You](https://foodtechconnect.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/infoGraphx-9174C-138-200x200.png)