Over the years we’ve cooked a lot of recipes. Some have called for a battalion of ingredients and some have even begged for certain items to measured within a tenth of a gram. Taken literally, a recipe inherently calls for some semblance of perfection in the kitchen–you have all the ingredients, all the equipment, all the spices, etc.–and depending on whose recipe you’re reading, deviating from the script can be hazardous.

This sort of cooking is fine and well for the situation that calls for it, but more often than not in our lives, we cook in a much looser format. Life isn’t perfect, we aren’t perfect, so why live under the engineered construct of cooking by the recipe, where the ante is usually some level of perfection that most kitchens don’t have?

And while I learned to cook to some extent by following recipes, what stuck with me has not always been the exact composition of a recipe, but the underlying structure that most good recipes follow. The simplest example is pasta. Why does Yummly need to show us 300 variations on Pasta Primavera? Why do we need 300 separate units of information to tell us how to make different versions of the same dish structure? The formula for Pasta Primavera is: 1) Pasta, 2) Vegetable, 3) Meat, if you wish. Why don’t we just tell people the basic structure of Pasta Primavera, tell them the characteristics of each element in the structure (e.g., Pasta: any long pasta works great, don’t use stuffed pastas; Vegetables: sturdy green veggies work best, don’t use potatoes…) and implore them to find the combinations that they like?

This is a question I aim to explore more. I believe that if you pay attention to how a dish is structured, rather than cooking each variation of it one by one in a recipe, you can have a much more fulfilling experience in the kitchen. You will gain intelligence about cooking, not just knowledge, and you will be more adept in the kitchen as a result.

A recipe is written like classical music–you follow the score, and note-by-note on the page, you create music. What I’m proposing is that we all start thinking of cooking more like Jazz–learn the basic scales and the right chords, then go off and jam out.

The Jazz approach brings cooking back down to Earth, embracing our culinary imperfections and whims, not making us feel bad that we don’t fit the rules dictated by a recipe. If we can teach people to become better improvisers in the kitchen, we can lower the barriers to cooking at home, and hopefully create new a new habit for the average American. I believe that we are smarter than the caricatures of chefs (professional and otherwise) that we see on the Food Network, and that we can teach people how to be intelligent in the kitchen, not simply follow orders.

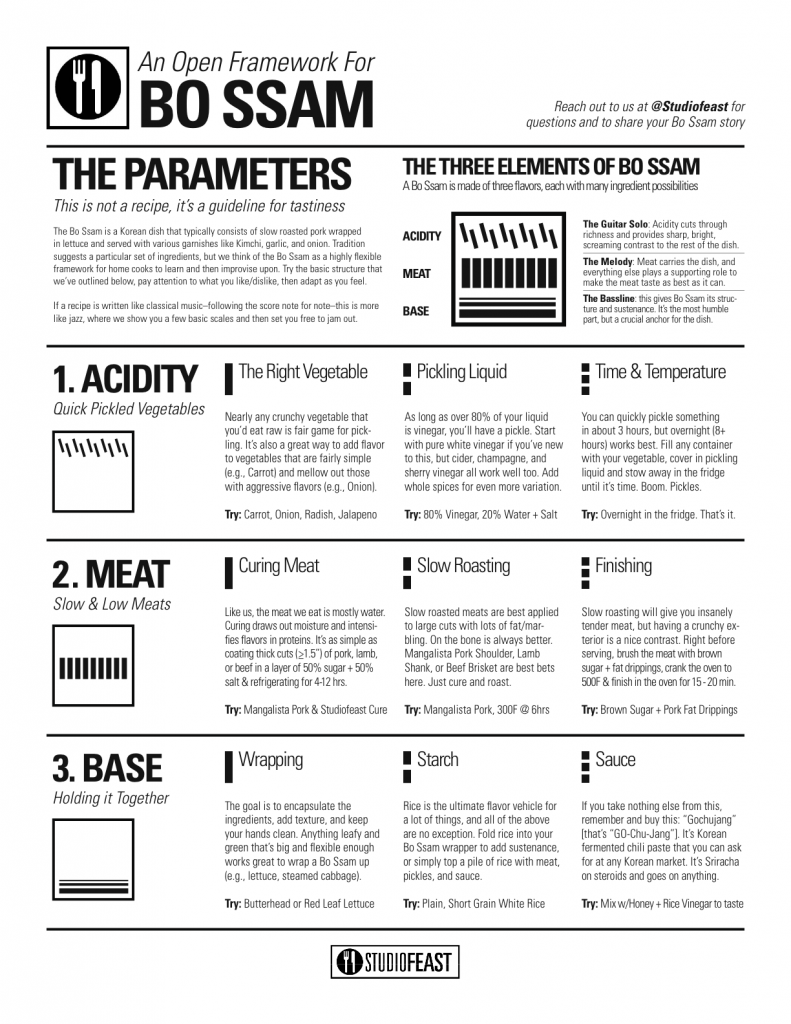

Which brings me to the image at the top of this post. Here is a structure for Bo Ssam, the carnivorous Korean classic that has sat at the center of many a dinner party for us. The key elements of a Bo Ssam are unpacked in the image above, but we try to give guidelines rather than instructions on how to create your own. It’s an imperfect, initial attempt, but I want to see if it makes sense to people and if it can be the first step toward getting people to approach cooking a different way. This is the start, and it will evolve.

Go on, download the Bo Ssam Framework here and try it on your own. Let us know on Twitter or in the comments below how you did.

[Check out the Studiofeast Cure for Meats, a limited edition giveaway at one of our recent dinners. There are some left in limited quantities, so email me if you’re interested in getting your hands on one.]

This post originally appeared on Studiofeast.