Yesterday, in part 1, I outlined how quickly the world of technology is changing. John set the bar by accessing open source code from Google and said: “Look, the map is up. Now what are we going to do with it?” It was now time for some programming tricks.

Yesterday, in part 1, I outlined how quickly the world of technology is changing. John set the bar by accessing open source code from Google and said: “Look, the map is up. Now what are we going to do with it?” It was now time for some programming tricks.

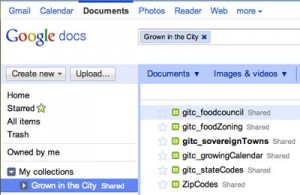

How were we going to store the data? At this point, I was in the frame of mind to say: “What can we do that is simple, easy, and most importantly, effective?” My answer: Google Docs.

What are the advantages? Nearly everyone knows how to use Microsoft Excel, so working with data in a spreadsheet is simple for a variety of users. Since it is stored “in a cloud” on the web, many people can edit it. Finally, the map tool we are using is also provided by Google, so the company has made it easy to access these “database” files from their map through a convenient API (application programming interface).

I had my solution in terms of where we’d store the data, but now I had to think about how.

Each map we were thinking about implementing would need to store certain data that is often the same – for example, the State. In complex database systems, I would implement a “lookup table” to minimize data redundancy. Well, we didn’t have a lookup table, but in a spreadsheet program, I could make the column have a dropdown box to choose the state. So, problem solved.

The next set of issues came from my preference to create stored procedures rather than dynamic SQL. Stored procedures may be great for huge scale systems, but all we wanted to do was to show a row of data on a map when the user clicks on the State. My stubbornness about always using a “correct methodology” would have to be stowed- we’re in the world of small apps now.

The interesting thing about making my life simpler was that I was getting to see it making everything simpler. By providing an online spreadsheet, both John and I were able to quickly edit items, sometimes at the same time (in Google Docs, you can actually see the other person’s edits while you yourself are viewing and editing the document). This also enabled us to have a nice repository of data. Since we didn’t need to create a front-end for us to enter data, we don’t have to know some specialized SQL querying language to enter the data. Other users can download the dataset and understand exactly what it means. While, my inner “programmer and database architecture” self was kicking and screaming “no!” my new “rapid development and execution skills” self was saying “yes.”

We now had a data repository that was not only platform independent, but also accessible from any device with a web browser. We were on to a new easier way to handle our data.

The last part of the data question was the sharing of data. This is probably where the most has changed since I started my career. We are in an age of information like never before. As a kid, a great way to learn new information was talking my mom into buying a new edition of the Science Encyclopedia at the supermarket. Now, a 14-year-old can go onto the internet and look up a topic for her Biology report from a source like Wikipedia (which may have been edited by hundreds of professors, engineers, and students alike into a wonderful informative piece of ever-evolving knowledge) or even go on to the website of a top university and read the exact text book that a PhD professor would be teaching from – or could even hit one button and have the entire syllabus in PDF format downloaded onto her computer or eBook in seconds. In a way, it’s not a problem of accessing the data, but rather, making sense of it.

The last part of the data question was the sharing of data. This is probably where the most has changed since I started my career. We are in an age of information like never before. As a kid, a great way to learn new information was talking my mom into buying a new edition of the Science Encyclopedia at the supermarket. Now, a 14-year-old can go onto the internet and look up a topic for her Biology report from a source like Wikipedia (which may have been edited by hundreds of professors, engineers, and students alike into a wonderful informative piece of ever-evolving knowledge) or even go on to the website of a top university and read the exact text book that a PhD professor would be teaching from – or could even hit one button and have the entire syllabus in PDF format downloaded onto her computer or eBook in seconds. In a way, it’s not a problem of accessing the data, but rather, making sense of it.

But, what is this push – why would a University release this data, that for centuries had been held behind lock and key? Only viewable by the financially privileged, or the intellectually lucky? Well, universities, businesses, and even the government are taking an entirely new approach to data management that is built around two very important ideas. The first is, “free the data, and new opportunities arise that have never been dreamed of.” That 14-year-old girl might read the presentations from an MIT course online at age 14, and the old way of thinking would be that she would then not want to go to college at that school and they would lose money. But this model of thinking is false. Instead, imagine that she not only ends up going to school there, but she is now ready for a more advanced course, or she has expanded upon the topic in new ways that has helped advance the subject matter.

Secondly, “freeing the data creates a level of transparency that can never be questioned.” When a government agency is willing to release all its findings and tell the public, “go ahead, crunch and analyze our data – find the errors for us, analyze it in new ways, and tell us what you find!” Now, instead of the four employees that normally would have studied this data, hundreds of people can analyze it. The government is getting work accomplished by outside sources, the outside sources are getting a sense of accomplishment, and what was once static data has now become a public domain resource that is constantly updated, refined, and most importantly built upon.

It is with these two mantras in mind that we built the interactive maps we’re currently working on. We view these as sources for people to input new data, extract the data and analyze it, and come back with new products we wouldn’t have even thought of.

Come back tomorrow, when I will discuss how to connect the data.

This post originally appeared on Grown In The City.

________________________