Photo: Gosia Wozniacka

Food+Tech Connect and The Future Market are hosting Biodiversity: The Intersection of Taste & Sustainability, an editorial series featuring interviews with over 45 leading food industry CEOs, executives, farmers, investors and researchers on the role of biodiversity in the food industry. See the full list of participants and read about why biodiversity in food is important here. We are also producing a biodiversity exhibit at The Winter Fancy Food Show, so please stop by to say hello.

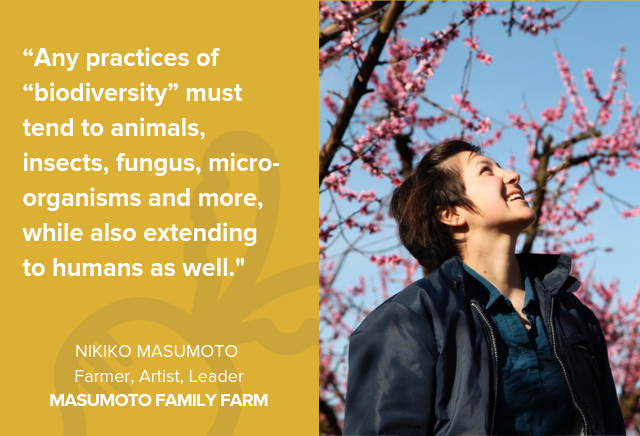

Nikiko Masumoto is a fourth generation, Japanese American farmer, artist and leader. Together with her father she raises organic peaches, nectarines and grapes for raisins on their family farm Masumoto Family Farm. Below, Masumoto poetically describes her love for the word biodiversity and all it encompasses. She also discusses industrial agriculture’s history of racism, slavery and patriarchy, urging us to include diversity of people in any conversation about biodiversity.

______________________

Danielle Gould: Is biodiversity a priority for Masumoto Family Farm ? If so, how and why?

Nikiko Masumoto: The term “biodiversity” is a marvelous word. When I pause to study its constitutive parts: bio, of life, and diversity, a full spectrum of differences — I am struck by the wish embedded in it. I wish for a world where we all sought to foster life of all kinds.

Yes, biodiversity is an essential way of being for us on the Masumoto Family Farm. There is no doubt, when take the measures to welcome life in its many forms, our farm is more resilient.

DG: How does Masumoto Family Farm define and think about biodiversity? What does an ideal biodiverse food system look like? How do you measure biodiversity, and when will we know when we’ve arrived at a “good” level of biodiversity?

NM: I think about biodiversity on our farm in terms of balances and healing. The term also invites me to think about the ways in which industrial agriculture, for much of the 20th and 21st century, has excluded or even tried to ‘sterilize’ fields of life (through monoculture and chemical applications aiming to eradicate) both non-human and human life alike. We have to remember the ideological linkages between monoculture, chemical dominance, and the history in this country of power and dominance.

Growing up as an Asian American in California, I was taught to understand the explicitly racist history of land policy in the place I call home. California Alien Land Laws of 1913 and 1920 prohibited Asian immigrants from owning land based solely on their race. American histories of genocide and forcing Native Americans onto reservations, of slavery, of patriarchy – all of these ideologies and their policies made clear what people were allowed or not allowed to exist in relationship to American land. From this vantage point, any practices of “biodiversity” must tend to animals, insects, fungus, micro-organisms and more, while also extending to humans as well. Advocacy and work towards biodiversity must include sharp critiques of social inequity, righteous policies to repair and redress grave wrongdoings, and warm gestures of healing.

Like any noble practice, working towards biodiversity will never be done. We can measure progress in restoration of life into our farmland, including things like native plant species, native insects and animals, wildlife habitat, and healthy living soils. Any progress is good, but I do not believe “biodiversity” is a box to check. It is a practice, a way of being, an orientation toward the world of welcoming and equanimity.

DG: What is Masumoto Family Farm doing or planning to do to promote biodiversity?

NM: We have used many practices developed in organic farming and related ecologically mindful research. To share a few: we have planted native species of plants, sown and encouraged cover crops, fallowed acreage, built owl boxes, and created habitat for native pollinators. There are still many things we can do, and hope to do.

DG: What is the business case for biodiverse agriculture?

NM: If we want to be able to grow food indefinitely, supporting biodiverse ecological systems is one of our best forms of building resilience. We have created many short-term insurance programs that take into account the inherent risks of farming (crop insurance), but we only need to extend our view to think about generations to see that biodiversity is akin to insurance for longterm ecological health.

DG: What investments need to be made to create a more biodiverse food system?

At every scale, there are simple and yet-to-be-discovered possibilities for investing in biodiversity. I could imagine all kinds of strategies, from both public and private investment, through incentives, awards, consumer demand. If there is a possible Green New Deal, what would it look like for public investment? Could we purchase land and make “biodiversity belts” across thousands of acres of farmland to re-create habitat and add a little “wild” to the mostly mono-culture landscape? The possibilities are vast if we can build the political will to act.

DG: What are the greatest challenges and opportunities farmers face for creating a more biodiverse system? What are you doing to overcome or capture them?

NM: There are different challenges for different contexts of farming. For some, it’s a challenge of vision and values; biodiversity just doesn’t weigh heavily enough. For others, it’s a challenge of resources, be they time, capital or expertise. Building practices into our normal routines on the farm that encourage biodiversity, even in small ways, is part of the shift we are interested in.

From the vantage point of opportunities: there is increased interest in holistic approaches to farming from cooks, chefs, and eaters. There are benefits to sharing and showing practices that encourage biodiversity. Many of the benefits seem to be available if we can tell our story effectively.

DG: How might we get more farmers to invest in biodiverse agriculture?

NM: Kitchen table conversations. Relational activism. Slowing down and creating opportunity for biodiversity to emerge as a shared need. This work might not even use the word biodiversity. It might look like conversations about someone’s grandchild who loves butterflies, and how might we make habitat for butterflies to enjoy on the edges of a farm. We must be as creative as we are kind, we must be as kind as we are fierce in our dedication to our vision of what agriculture can do.

DG: What are some of the most important things food manufacturers, retailers, chefs and other key actors across the food supply chain can do to support biodiverse agriculture?

NM: People and organizations involved in the food system play an important role for farmers: these relationships are the human connections of the food chain. Encouragement and recognition from these partners is powerful.

DG: What is your vision for what a more biodiverse food system looks like in 10-15 years?

NM: I see more native plants, more habitat for pollinators, more small operations growing a wider variety of food, less chemical use, more life in all its forms. I hear birds and insects, joy in the fields.

Read all of the interviews here and learn more about Biodiversity at The Future Market.

______________________________

Nikiko Masumoto, Farmer, Artist and Leader

Nikiko Masumoto, Farmer, Artist and Leader

Nikiko Masumoto first learned to love food as a young child slurping the nectar of overripe organic peaches on the Masumoto Family Farm. Since then, she has never missed a harvest. Farmer, artist, and leader, Nikiko works alongside her father to raise organic peaches, nectarines and grapes for raisins. She is adding a fourth (yonsei) generation’s voice to the story of the Masumoto Family Farm and the Central Valley of California. She’s contributed to two books: The Perfect Peach (Ten Speed Press) and Changing Season (Heyday). With Brynn Saito, Nikiko co-founded Yonsei Memory Project which aims to awaken the archives of Japanese American history and enact healing and justice through art. She serves on several arts organization boards, is a past recipient of National Arts Strategy’s Creative Community Fellowship, and most recently, received a spot in Entrepreneurship Intensive for Farmers at Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture. Nikiko is a fire-spirit, feminist farmer, civic practice and agrarian artist.