The conversation about the future of food has exploded over the past half decade. Much ink has been spilled examining virtually every new food innovation from lab grown meat, to soil-free indoor farms, to new forms of genetically modified foods.

One of the forces behind this food tech movement are a legion of starry-eyed entrepreneurs fueled by millions in venture and corporate funding, looking to transform this $5 trillion industry into one that’s more efficient, sustainable, delicious, and healthy.

But just as many of these new, high-tech ideas will have a big impact on the future of food, so will many older, lower-tech ideas that have resurfaced into the zeitgeist. One quick walk down the supermarket aisles is a reminder of how the food industry aspires to produce simpler, more wholesome food that evokes attributes of the past, before food became an industry.

Organic. Free Range. Grass-Fed. The premium buzzwords of today simply describe how all food, by default, was made yesterday. What’s old has become new, but as we continue this conversation about the ideas that will carry us into the future, one very old concept is surging back into the food dialogue: food biodiversity.

The Intersection of Taste and Sustainability

Food Biodiversity, or more specifically, agrobiodiversity, is defined as the variety and variability of the plants, animals, micro-organisms, and biocultural systems linked to food. That’s the technical definition.

This variety and variability brings strength and resilience to food ecosystems, as it’s much harder to bring down a system where a diverse constituency of organisms both support and compete against one another to advance the health of the ecosystem.

The Irish Potato Famine is a stark reminder of what can happen when a critical food source lacks biodiversity, as a single disease was able to wipe out enough of the monocultured potato supply that 1 million people died of starvation and sickness.

Biodiversity is crucial to the health and safety of our food supply. But to us, biodiversity in food means something even more. Biodiversity sits at the intersection of taste and sustainability, where we can simultaneously satiate an eater’s desire for new, interesting foods, while supporting a more diverse cornucopia of foods being cultivated in the world.

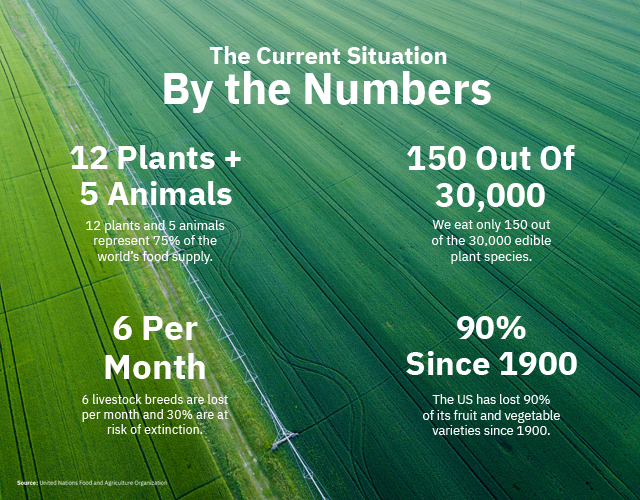

Globally, 75% of our food comes from just 12 plants and 5 animal species. This enormous level of consolidation around just a handful of food sources not only magnifies the impact of any attack on the food supply — like the Irish Potato Famine — but it also consolidates our taste buds around just a few flavor experiences.

Of course, these few ingredients are remixed within the industrial food complex as a diverse ecosystem of brands, which gives the illusion that we’re eating from variety, but there is so much more to taste and experience in the world.

Eating from a more diverse selection of foods can reduce our reliance on the small handful of industrialized crops for our sustenance. For example, creating more demand for foods like Moringa, a nutrient-dense superfood from Southeast Asia, Fonio, a drought-resistant ancient grain from West Africa, or Kernza, a deliciously sustainable grain from the United States, provides a chance to simultaneously enrich our bodies, our planet, and the communities that cultivate these foods.

These foods are all great places to start, but they’re just the tip of the iceberg, as we humans in aggregate only eat 150 out of 30,000 edible plant species which leaves an entire world of flavor to explore.

Sustainable, Biodiverse, and Selfish

Forging a closer union between food that sustainably bolsters biodiversity and food that’s selfishly delicious, is a formula that will enable the sustainable food movement to truly attain scale and longevity. You can get a lot of people on board for a cause rooted solely in altruism, but you can get even more if you can also tie that cause to a selfish benefit.

These two causes — one altruistic, one selfish — need not be mutually exclusive. For example, Patagonia Provisions’ Long Root Ale, the first beer to be made from the environmentally enriching grain, Kernza, is a great example of how we can do right by our taste buds and the planet. A more biodiverse food system simply grows our opportunities for more products like Long Root Ale.

This approach of making more irresistibly delicious foods, that enrich the individual, from more sustainable or regenerative ingredients, that enrich the planet, is necessary to further mainstream the idea of food that’s great for people and planet.

In food, great taste gives you the license to promote other virtuous causes, and flavor is the vehicle that will bring us to a more biodiverse and sustainable food system.

To Learn More About Food Biodiversity:

- Biodiversity, an online exhibit at The Future Market

- Join the conversation at #biodiversefood