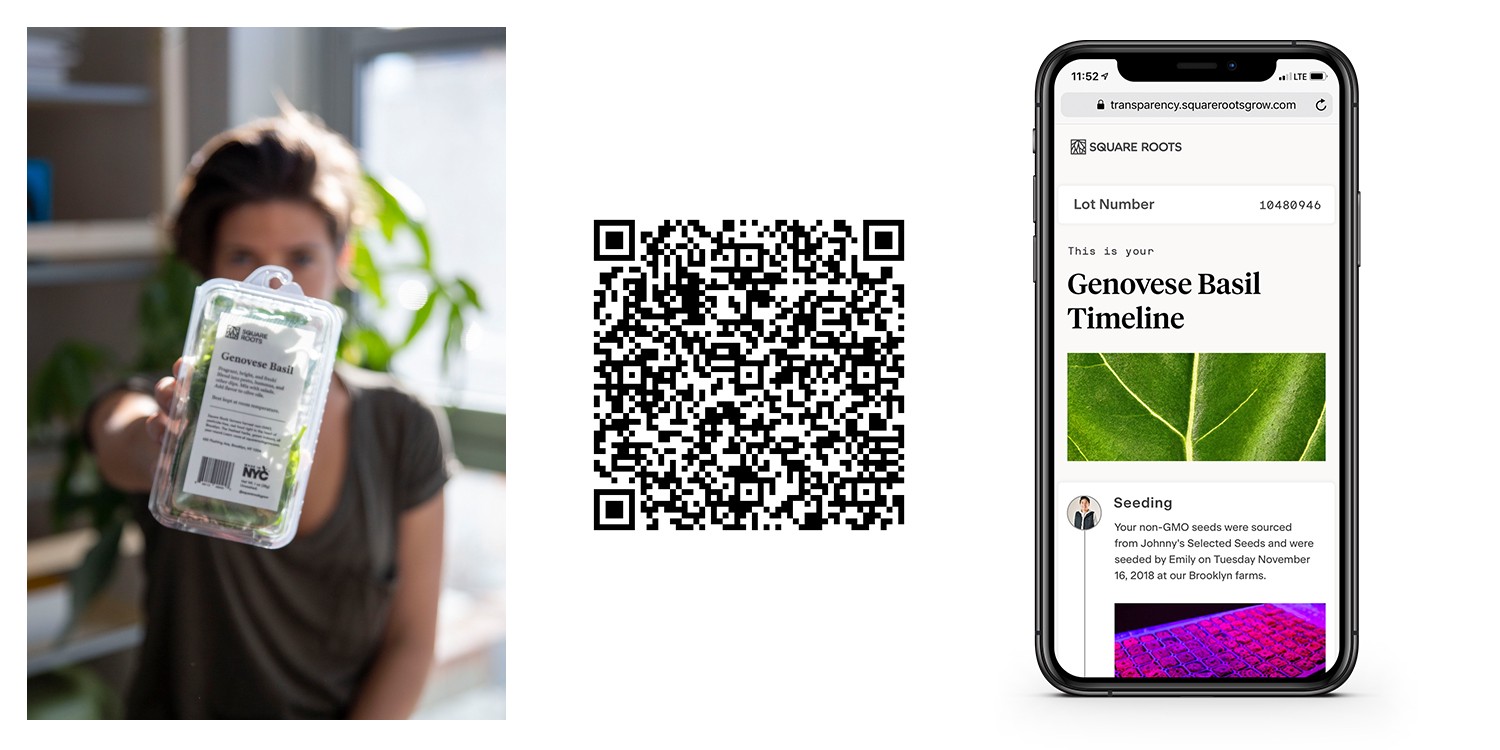

Square Roots Transparency Timeline via Square Roots

Food you can trust.

We can all remember the Thanksgiving romaine lettuce recall. It put millions of consumers at major risk of foodborne illnesses. The situation was compounded by opaque supply chains in the Industrial Food System, making it ridiculously difficult to accurately trace the source of guilty pathogens. To their credit, the big lettuce producers did eventually react, and agreed to start labeling their products with a mark of the state in which their products are grown. But that’s not enough. Consumers want food they can trust.

It’s common today to see companies telling consumers “you can trust our food.” That never sits comfortably with us. “Trust us” can’t be an instruction. Trust has to be gained. And one way for a food brand to start gaining trust is by being transparent, by opening up data, and by giving consumers all the facts. When it comes to produce, for example, what people want to know is: where and how was my food grown, who grew it, and when? With that data, people can make their own informed choices about whether to trust the food and whether to buy it.

We have that data at Square Roots. After the romaine recall, we realized we should make it available to our customers.

Sharing insights and learnings.

In the spirit of sharing insights and learnings that are hopefully helpful to others in the Food+Tech Connect community, this post shines a light on how we made this data accessible to customers, and also covers some of the technology decisions we made along the way.

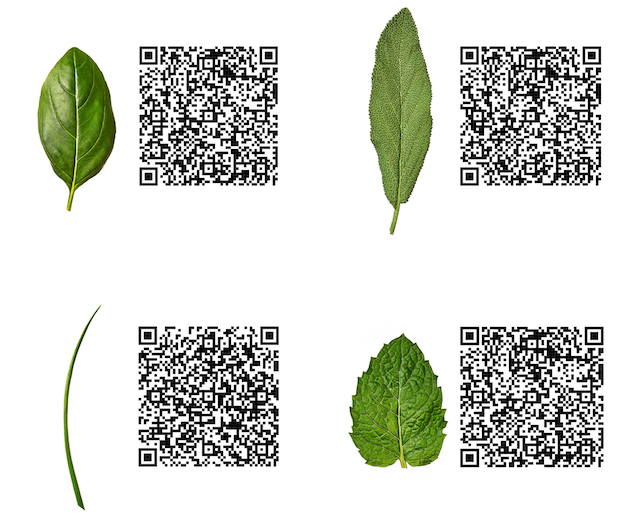

For those not familiar with Square Roots, we are an indoor urban farming company headquartered in Brooklyn, NYC. We grow a range of herbs – like basil, mint and chives – and distribute them directly to retail stores across the city within a day of harvest. At the heart of Square Roots is our Next Gen Farmer Training Program, which provides a launchpad for young people to enter the farming industry. Meanwhile, our farms are constructed inside refurbished shipping containers, each with its own programmable climate—meaning we grow food all year round, with zero pesticides.

To help us train young farmers, we’ve developed our own software layer, which we call The Farmer Toolbelt, that provides instructions and insights to help the farmers with their day-to-day activities. Our farmers access The Toolbelt via tablets in the farms—and the software might tell them, for example, what tasks need completing in the farms that day, based on models we’ve built to optimize the growing cycle of certain crops. The Toolbelt is also used to capture data at every step of the process—such as who completed what task, when, how long it took, and more. As a result, we’re able to trace a direct line from every seed we sow to every package we sell. All that data is then analyzed against factors such as the quantitative impact on eventual yield, and the qualitative impact on taste, which helps us develop even more effective growing models over time.

Nate Burt on our engineering team was hacking on the Toolbelt’s backend data over Thanksgiving when the romaine recall happened. He saw the furor unfold as consumers got scared and millions of dollars of perfectly good produce got pulled from the shelves—all because no-one could swiftly trace the source of the issue.

Nate immediately understood that we could open up elements of our data set, expose it to consumers, and show a complete timeline—tracing where and how the food is grown, and who grows it. He built V1 of what we now call “The Transparency Timeline” that weekend, and showed us all when we came back in the office post-Turkey coma.

Transparency Timeline QR Codes via Square Roots

To blockchain or not to blockchain?

When you hear the words “transparency” and “traceability” in food-tech circles, people often jump to the conclusion that blockchain is the right solution. We certainly had to think that through when assessing the viability of Nate’s V1.

We’ve been tracking this technology closely for a while. Inspired by Mike Lee, I’d written about its uses for food traceability on my personal blog last year. But our feeling is that “blockchain for basil” isn’t quite ready for primetime yet. Initial implementations from Big Food companies have been heavily buzzword-compliant but are distinctly underwhelming in terms of the useful information they provide.

There’s another irony with the blockchain buzz. Architecturally, it could be a neat solution to provide traceable information about industrially-produced food—which can travel for weeks to get to the consumer while passing through multiple vendors performing multiple processing steps along the way. But, increasingly, consumers are turning towards local real food, precisely because there are fewer steps in the supply chain and they trust it more. It’s almost like blockchain is a new solution for the old food system that consumers are moving away from.

At Square Roots, for example, all our products are sold at retail stores within four miles of our farm, and we own every step from seed to shelf; there are no third parties or handoffs along the way. As we scale, we will keep building local farms in the same neighborhood as the consumers — so we can always own the supply chain end to end.

Even though we’re optimistic about the long term vision for the wider food industry, the reality is that we, like many local farmers, don’t need to utilize blockchain architecture to give the consumer what they want today—total transparency, without the need for buzzwords. Even the blockchain vendors recognize that.

Going from internal demo to full product.

On December 1, we made the decision to take Nate’s V1 and turn it into a real product. The functionality would be simple, but really powerful. Every package we sold would have a QR code on it. The QR code would be associated with the data set for that particular package, as captured in The Farmer Toolbelt. Consumers would scan the code with their phone, and a mobile web page would pop up showing a complete timeline of where and how your food was grown, and who grew it.

QR codes are commonplace for consumers in Japan and China, but have been slow to take off in the US. However, now that Apple has integrated a QR code reader right into the native camera app on the iPhone (you simply need to point your camera app at the code and it gets read instantaneously), adoption is increasing here. In the retail setting, it’s easy for consumers to take out their phone, scan the code, and quickly learn more about the food they might buy. However, to make the Transparency Timeline feature available to everyone—even non-adopters—we also built a page on the Square Roots website where customers can manually type in the lot number found on the package and see the same information.

Our systems also track what happens to every clam shell as it get packaged, leaves the farm, and heads to the store. So we are able to show the complete story of the food from seed-to-shelf.

We launched the Transparency Timeline on December 19.

That sounds fast, but remember that we haven’t had to invent new business processes or technologies to make this happen — we’re just exposing the data we already capture in the Farmer Toolbelt as part of our everyday operations.

Launching, of course, didn’t just mean designing the UI and building the backend app. We had to change our labels to make sure every package now had a QR code. And we trained our farmers to explain things to our customers and retail partners. We’ve only got 17 full time staff at the company, so the initiative probably touched everyone at some point during the 3 week sprint to pull it together.

But it’s been totally worthwhile. It’s a whole new level of transparency. It’s all about consumers getting the information they need to make their own informed decisions about food they can trust.

_______________________

Tobias Peggs, CEO and co-founder at Square Roots

Tobias Peggs, CEO and co-founder at Square Roots

Tobias is cofounder and CEO at Square Roots – the urban farming company, headquartered in Brooklyn, NYC. He was previously CEO at Aviary, a mobile photo editing company (acquired by Adobe); and CEO at OneRiot, a social media analytics company (acquired by Walmart). Tobias has a PhD in Artificial Intelligence from Cardiff University in his native UK. He is a Techstars mentor, competitive triathlete, snowboarder, and eats far too much ramen.