This is a guest post by John Foraker, President of Annie’s, Inc.

Right before the U.S. equity markets opened on Friday, June 16th my phone erupted with texts from numerous industry friends on the announcement of the Amazon acquisition of Whole Foods. I have been in this industry for decades, and, for me, this was one of the most exciting and interesting days I can remember for the organic movement, certainly since the release of the USDA organic standards in 2002.

This deal has so many implications for the industry it is mind numbing. Total and complete #gamechanger. Who will be the biggest winners and losers? Will this make it even easier for highly disruptive challenger brands to grow and mainstream? What will the impact be on local organic systems and on the scaling of organic acreage globally? What are the implications for technology enabled food transparency? What will happen to pricing organic price premiums across the industry?

Those and so many more…But there was one monster question that popped into my head and rolled around with both fascination and optimism: Will this combination mark the beginning of the end to the tragic problem of food deserts in the US? Let’s explore that possibility.

The U.S. Food Desert Challenge

Food deserts are communities where access to affordable, quality, and nutritious foods is limited. More than 23 million Americans, including 6.5 million children, live in low-income urban and rural neighborhoods that are more than a mile away from a supermarket. In these neighborhoods it’s easy to buy 44’s, cigarettes and fast food, but fresh produce and other healthier food options? Not so much.

Is there really a food access problem? There sure is. America’s top 75 food retailers – led by Wal-Mart, Kroger, Costco, Target and Safeway – opened more than 10,000 new locations between 2011 and the first quarter of 2015, according to a 2015 analysis published by The Associated Press. When the AP stripped away convenience stores and dollar stores that don’t usually provide fresh meal options, it found that only a little over 250 new supermarkets cropped up in the country’s expansive food deserts. The takeaway: traditional retailers have not been meeting the healthy food needs of those who need it most.

And then there is the issue of the costs of living far from a grocery store. A study published in the Agricultural and Resource Economics Review finds that “lower-income shoppers must travel further and/or have fewer shopping options than do higher-income shoppers.” Fewer shopping options generally equates to less intense pricing competition for local stores, which could allow grocers to boost prices or offer products of poorer quality. Higher costs for better food leaves low-income shoppers with fewer choices.

There is clearly a monumental #foodjustice problem, so how are individuals and businesses solving it?

One citizen who is fighting for food self determination is the courageous “Gangster Gardener” Ron Finley of South Central Los Angeles, who became famous for fighting the Los Angeles bureaucracy to allow citizens to grow food on public parkways in their own neighborhoods. Finley’s powerful message to “plant some shit” and grow your own food became a global sensation with this inspiring TED talk. Local self-empowerment and the education about healthy food that accompanies it is most definitely a big part of the solution, but will it alone be enough, fast enough?

Some incredible businesses have emerged to increase the availability of healthier foods in low-income communities through online delivery models. Thrive Market, for example, a membership-based online buying club that sells natural and organic products at reduced costs, is on a growth tear as it pursues its mission “to make healthy living easy and affordable for everyone.” For every new membership Thrive donates a membership to a low-income family, teacher, veteran, or student. But can highly successful, relatively small online players alone really make a dent in such an enormous problem fast enough?

Brick and mortar retailers like Whole Foods have also tried to improve access in recent years, stepping outside their historical comfort zone and opening physical stores in underserved places like Detroit. Former Whole Foods Co-CEO Walter Robb said when addressing corporate leaders at the Milken Institute Global Conference that at the Detroit store “we’re going after elitism. We’re going after racism.” Real success, Robb said, would include improvements in health outcomes. Opening Whole Foods stores like this in many more food deserts requires a lot of capital and they are slow to build and drive impact. Beyond that, even though these stores have been a commercial success, prices are still high relative to the limited consumer incomes in these areas, as Slate outlines. But Whole Foods’ cultural commitment to attacking this problem is real, admirable and deeply rooted. Through its Whole Cities Foundation, a non-profit founded in 2014, it works to “improve individual and community health through collaborative partnerships, education, and broader access to nutritious food in the communities we serve.”

Amazon + Whole Foods Market = Golden Opportunity to End Food Deserts

Back to the Whole Foods-Amazon combination. What promise does the merging of these companies hold to attack food access issues? The potential is simply immense.

Amazon has been investing heavily in Amazon Fresh’s capabilities to deliver groceries at scale. This delivery infrastructure, coupled with its focus on driving down costs for consumers and its use of data analytics to target offerings to shoppers, are exactly the tools that can bring healthier food options to the front door, or landing target (in the case of drones), to any corner of any underserved neighborhood anywhere. This alone is a great start. But when you combine this delivery infrastructure with Whole Foods’ 450+ stores and organic food supply chain, you enable the delivery of natural and organic foods to most places in the US in a matter of an hour or two. Given Whole Foods’ deeply rooted cultural commitment to addressing food deserts, this acquisition has the magic potential to address this difficult problem. It will take a while, but I expect the combined company to make this a priority, and that it will indeed drive significant impact in the affordability and accessibility of good food in every neighborhood.

Access Alone is not Enough

We also know, however, that access alone will not improve food choices and health outcomes. According to a 2014 PBS article entitled Why It Takes More Than a Grocery Store To Eliminate A Food Desert, the problem may not lie solely with food accessibility; it is also due to shopping and eating habits developed over many generations. In the article, Steven Cummins, a professor of population health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, suggests that merely adding a new grocery store to a neighborhood won’t be enough to motivate individuals to shop there for healthier foods. “If you think about Kevin Costner in the Field of Dreams — ‘If you build it, they will come’ — I guess that’s the kind of logic model that underpins these interventions. But that doesn’t do everything it’s supposed to do,” he says. “It can improve perceptions of food access, but it doesn’t necessarily translate into a behavior change.”

The educational and grassroots orientation of Whole Cities Foundation and countless other local organizations will be needed to educate consumers about making healthier food choices. I sincerely hope Amazon’s leadership team will understand the potential they have to educate their customers. The potential for societal change is significant, and the investments will be worth it. There are plenty of willing partners ready to get after this big mission, and all that is needed is a catalyst and a focal point for the work. There is a tremendous leadership opportunity available to Amazon if they choose to grasp it.

The also government needs to play a role in furthering education about healthy food in schools, while driving changes in school menus. In the absence of federal leadership, states and localities need to pick up the slack and continue to fight.

Large food companies like General Mills and their organic businesses like Annie’s need to continue to direct resources and passion to this problem. Pioneering organizations like Food Corps need to be scaled dramatically to overcome the educational and behavioral barriers to healthier food adoption. Together, all these groups can connect kids and families to real food. All of these things need to happen in unison for significant change to happen.

A Call to Action

The combination of Amazon and Whole Foods has the potential to make a big difference in food deserts, but they cannot do it alone. We need to leverage this new capability with help from all levels of government, the private sector, the engagement and commitment of passionate local activists like Ron Finley, combined with significant public & private sector investment to unlock it. Big problems are never easy to solve, but this is one I firmly believe can be overcome in my lifetime.

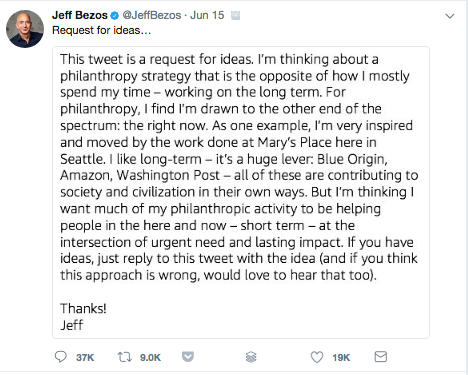

Two days ago, Amazon Founder and CEO Jeff Bezos Tweeted the following message:

Jeff, here’s my idea. Post-merger, host a big summit called something along the lines of “Eliminating Food Deserts in the U.S. by 2027”, invite all the parties that can help make that happen, and build a plan to do it using the Amazon-Whole Foods platform as the backbone.

Let this be the decade of now.

________________________

John Foraker is President of Annie’s, Inc, a leading natural and organic food company based in Berkeley, CA., now an operating unit of General Mills, Inc. Annie’s is a mission-driven business focused on sustainability, social responsibility, and delighting our millions of fans. Foraker holds an M.B.A. from the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkley (1994) and a B.S. in Agricultural Economics from the University of California at Davis (1986).

John Foraker is President of Annie’s, Inc, a leading natural and organic food company based in Berkeley, CA., now an operating unit of General Mills, Inc. Annie’s is a mission-driven business focused on sustainability, social responsibility, and delighting our millions of fans. Foraker holds an M.B.A. from the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkley (1994) and a B.S. in Agricultural Economics from the University of California at Davis (1986).