Hacking Meat is an online conversation exploring how can information and technology be used to hack (or reimagine) a more sustainable, profitable and healthy future of meat. Join the conversation and share your ideas or product requests in the comments, on Twitter using #hackmeat, on Facebook or at the Hack//Meat hackathon happening December 7-9 in NYC.

By Chelsea Bardot Lewis, Vermont Agency of Agriculture, and Samuel K. Fuller, Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont

As more consumers are using their food dollar to vote for a meat value chain that strengthens local economies and promotes environmental sustainability, producers in Vermont and across the country have responded to this demand. According to Vermont’s Farm-to-Plate Strategic Plan, the total inventory of livestock raised for meat increased by 46% between 1997 and 2007, indicating significant growth in the industry over the past decade. This growth is promising, but it has not in all cases translated to an analogous growth in net income for producers and processors.

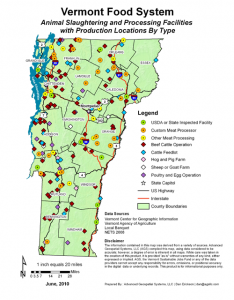

As opposed to the vertically integrated and consolidated commodity meat supply chain, the niche meat industry can be a somewhat chaotic web of differentiated producer brands, independent processors and diverse market channels. As new producers emerge, many are expressing a challenge in accessing processing capacity, and understanding the regulatory framework that applies to their market channel. While production in some areas may have expanded to a point that requires new commercially inspected slaughter and processing facilities, there is also a need enhance both the physical infrastructure and business savvy of existing plants.

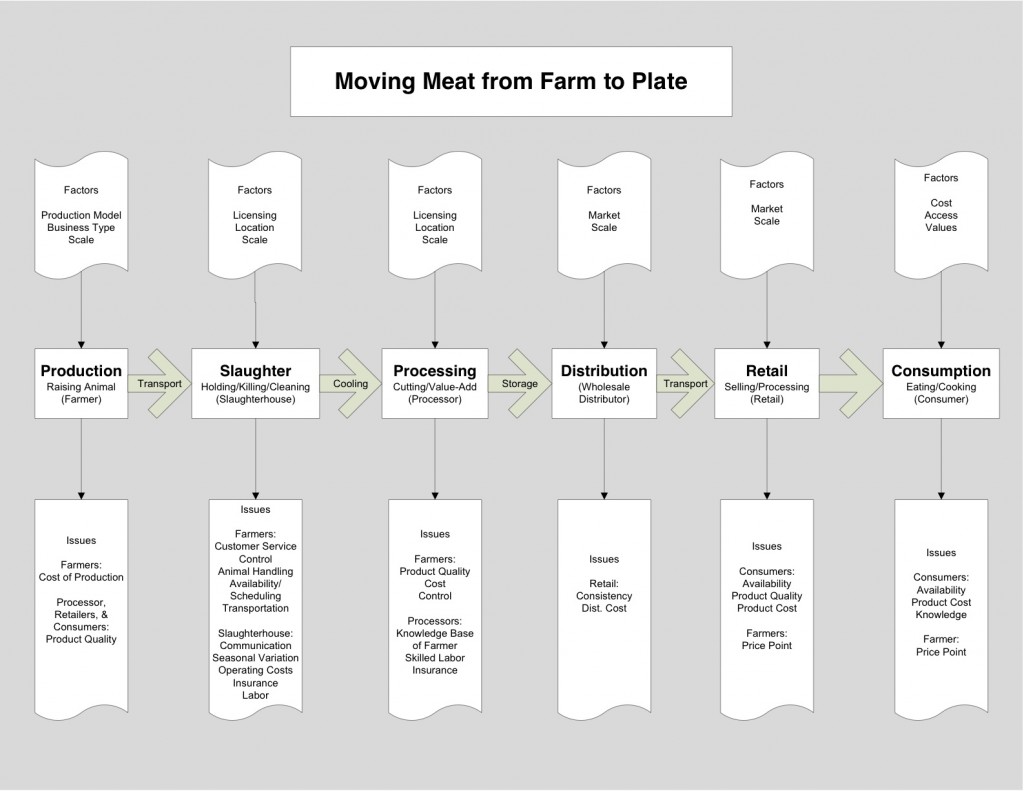

A value chain approach brings producers, processors, distributors, and end users together as co-producers in the niche meat market. Incorporating innovative technology into the value chain is crucial to a better coordinated, more efficient and more accessible local meat system.

2010 Inventory of Vermont Meat Processing by Samuel K. Fuller

We are engaged in a conversation around tech for meat at a time when very few small-scale processors utilize email, at least not on a reliable basis (most emails we send to processors are followed by a phone call to ask them to check their inbox). Not all of them have a website, and those who do seldom have the time to update them. These examples are just the surface of under utilized technology in the sector.

This current tech gap is an opportunity for a few elegantly simple solutions to leverage exciting impacts in the value chain.

Promoting producer-processor partnership

In this industry, producers and processors are fundamentally linked. They depend on each other for their respective successes, and must trust each other in order for the system to run smoothly. Expectations on processors are increasing as producers enter more discerning markets with higher value product. The growth of the value-added meat industry depends on solid producer-processor partnerships.

Food safety and security necessitate many solid walls and closed doors in the meat processing environment. However, processors are eager for both producers and consumers to know more about what they do. Technology can play an important role in improving marketability through transparency to the consumer and building relationships throughout the value chain.

For instance, could we increase transparency and traceability through the plant through GPS tags or other systems? Could scale-appropriate inventory management systems help both producers and processors help batch orders and track carcass yields?

Additionally, too often producers and processors default into antagonistic roles because they don’t fully understand each other’s business models. Visual representations of scale and stage of development might help producers and processors form smarter partnerships.

Finally, better data on niche meat production, processing, and distribution would help businesses across the value chain make more strategic investments to match supply with demand.

Optimizing Capacity Utilization

Research that we conducted in 2010 found that Vermont slaughter and processing facilities operated from 30 to 80% capacity during the off-season (February to August) and that on an annual basis, New England’s collective commercial kill floor infrastructure operates at only a 38% utilization rate, while on-site commercial processing (cut and wrap) capacity is much closer to full utilization at 78%. These asse

ssments find that there is a need to develop more robust models for year-round livestock production, slaughter, and meat processing.

Can systems be created that help processors indicate their availability to producers? Are there data management tools to help individual firms, sectors and value-chains be more collaborative and transparent? To create mechanisms that link available kill floor capacity at slaughter facilities to off-site processing-only facilities or incentivize processing during the off season?

Food Safety and Regulatory Compliance

An important best practice for minimizing food safety risk is implementing product traceability protocols. As mentioned above, customized inventory management systems could assist these businesses to increase their professionalism, as well as provide trackback functionality in the case of a recall. Few, if any, small-scale meat processors utilize this type of software.

Additionally, plants must find science-based literature to validate the controls they have included in their HACCP plan. While large-scale processors have departments dedicated to HACCP validation, in small-scale plants this responsibility often falls to an already overtaxed owner or manager. However, because many plants are using similar food safety interventions, the solution could be crowdsourced.

Can tech promote sharing among processors to solve challenges posed by new regulatory requirements?

Connecting Consumers to Producers and Processors

The growth of meat production and processing in Vermont will depend on how well we are able to connect with urban and suburban consumers. This requires enhanced systems for aggregation and distribution that are efficient at delivering the product to the end consumer while maintaining their value and connectivity to the consumer.

What communication tools or technologies are available to better communicate the production and processing of meat to the consumer? How can the consumer become a co-producer when they are no longer in ‘direct’ contact with the farmer? How can the farmer participate in the community of eaters without actually being at the table? With farmers looking to scale up and access wholesale regional markets, how can they be part of the community of eaters the serve?

We are excited to pursue the ways that technology can help answer these questions and catalyze the development of the niche meat value chain.

Join the conversation and share your ideas or product requests in the comments, on Twitter using #hackmeat, on Facebook or at the Hack//Meat hackathon happening December 7-9 in NYC.

___________________________________

Chelsea Bardot Lewis is a Senior Agricultural Development Coordinator with the Vermont Agency of Agriculture. She coordinates the Vermont Meat Processing Task Force, and facilitates value chain partnership between meat producers, processors and marketers in Vermont and New England. She has an M.S. in Agriculture Food and Environment from the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, where she conducted the research for “A capacity assessment of New England’s

Chelsea Bardot Lewis is a Senior Agricultural Development Coordinator with the Vermont Agency of Agriculture. She coordinates the Vermont Meat Processing Task Force, and facilitates value chain partnership between meat producers, processors and marketers in Vermont and New England. She has an M.S. in Agriculture Food and Environment from the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, where she conducted the research for “A capacity assessment of New England’s

large animal slaughter facilities as relative to meat production for the regional food system,” published in 2011. She and her husband Nate own Moonlight Farm in Waterbury, Vermont, an organic fruit and garlic operation.

Sam Fuller works for the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont where he coordinates the Farmer Technical Assistance Program. This program offers business planning, technical support, and education to dairy and livestock farmers in Vermont. Sam also plays a role at the state and regional level helping guide value-based meat industry development. Prior to coming to NOFA-VT in 2006, Sam managed a number of farm enterprises and moonlighted as an artisanal meat processor.

Sam Fuller works for the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont where he coordinates the Farmer Technical Assistance Program. This program offers business planning, technical support, and education to dairy and livestock farmers in Vermont. Sam also plays a role at the state and regional level helping guide value-based meat industry development. Prior to coming to NOFA-VT in 2006, Sam managed a number of farm enterprises and moonlighted as an artisanal meat processor.

-

Londa Vanderwal Nwadike December 4, 2012 at 4:32 pmSounds great! A great topic- lots of important questions that need to be answered.