Hacking Meat is an online conversation exploring how can information and technology be used to hack (or reimagine) a more sustainable, profitable and healthy future of meat. Join the conversation and share your ideas or product requests in the comments, on Twitter using #hackmeat, on Facebook or at the Hack//Meat hackathon happening December 7-9 in NYC.

Guest post by Patty Lovera of Food & Water Watch

I’m probably the last person in the world who should talk about technology. (As opposed to the “early adopter,” I’m more of a very late, extremely reluctant adopter.) But I’m much more equipped to talk about information and how we can use it to re-imagine the future of meat.

I work for a group called Food & Water Watch and we have lots of ideas about what’s wrong with the meat system. It’s exciting to see lots of folks figuring out better ways to produce and market meat. But at the end of the day, we’re convinced that we can’t shop our way out of this problem – we need to change the bad policy that has gotten us here. A first step is helping people understand the problem. And then we need them to get involved to help solve it.

One of the first things we want to help consumers understand is that the meat they buy at the grocery store probably didn’t come from a farm that looks anything like the picture on the package. The meat case gives the impression of a wealth of options, but the sad truth is the industry giants who dominate the meat marketplace dictate the type of meat we buy and which producers supply it.

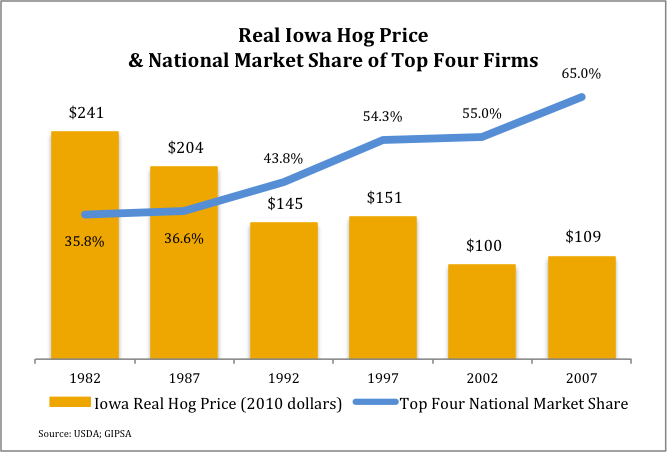

A lack of real competition among meatpackers and processors continues to squeeze out independent small-and-medium-sized livestock producers in favor of factory farms. At the local level, there are often only one or two meatpackers buying livestock and often both companies are represented by the same person, making it impossible for a farmer to negotiate a fair price. This had radically changed the game for independent livestock producers and small or medium-sized meatpacking plants, and many of them don’t survive the transition.

Iowa serves as a good example. In 1992, less than a third of Iowa hogs were raised on factory farms, but by 2007, 95 percent of the 18 million hogs produced in Iowa were. Over the same period, Iowa has lost around three fourths of its hog farms. So while the number of hogs produced went up, the number of farms producing them went down. And those farms that remain got much bigger.

Far away from the rural communities going through the economic and social changes brought on by the disappearance of family farms, consumers are slowly becoming aware of the downsides to this new model: water and air pollution, antibiotic resistance and massive food recalls. But what most consumers don’t yet know is that it’s not an accident that the structure of the livestock industry has changed and it’s not some breakthrough in efficiency. It is the result of unfair practices by large meatpackers, while regulators look the other way.

Overwhelming market control by a handful of corporations has lead to widespread abuses, including sweetheart deals for favored factory farms and feedlots. These types of special deals were supposed to be outlawed by the Packers & Stockyards Act of 1921, but 80 years later the law still isn’t properly enforced. In 2010, the USDA proposed rules to address some common market abuses by meatpackers. But under tremendous pressure by the meat industry, the Obama Administration and Congress gutted the rule.

Working on local food and alternative supply chains are absolutely necessary to rebuild pieces of our food infrastructure that have been lost. But they cannot do it alone. Once we educate consumers about what’s broken, we need to recruit them into a food movement that has the political clout to fix our broken food policy so family farm livestock producers can compete on a level playing field.

Patty Lovera is the Assistant Director of Food & Water Watch. She coordinates the food team. Patty has a bachelor’s degree in environmental science from Lehigh University and a master’s degree in environmental policy from the University of Michigan. Before joining Food & Water Watch, Patty was the deputy director of the energy and environment program at Public Citizen and a researcher at the Center for Health, Environment and Justice.

Patty Lovera is the Assistant Director of Food & Water Watch. She coordinates the food team. Patty has a bachelor’s degree in environmental science from Lehigh University and a master’s degree in environmental policy from the University of Michigan. Before joining Food & Water Watch, Patty was the deputy director of the energy and environment program at Public Citizen and a researcher at the Center for Health, Environment and Justice.